Early Years and the Founding of the Workshop

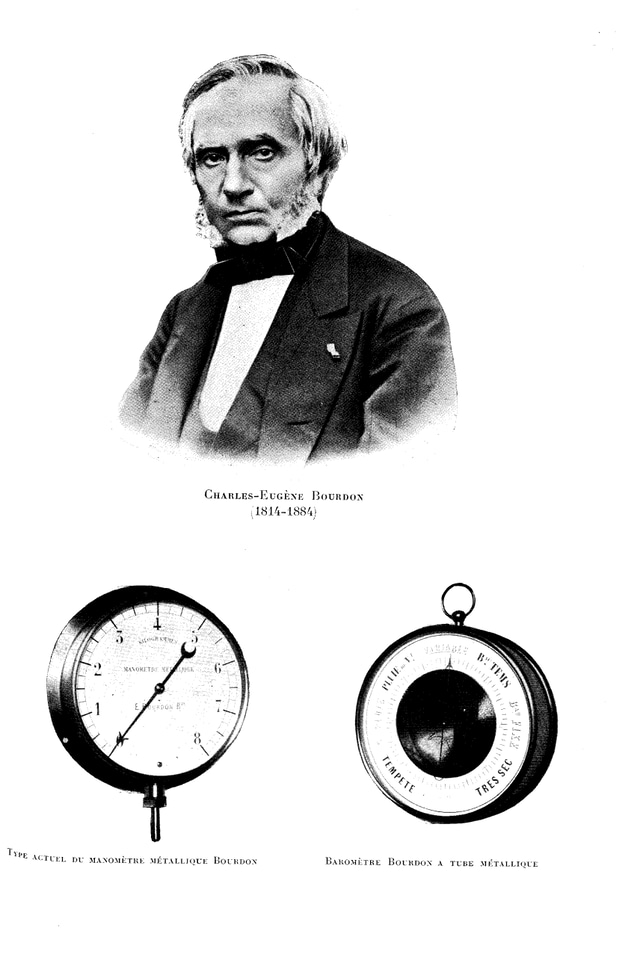

Eugène Bourdon (full name: Charles Eugène Bourdon) was born on April 11, 1808, in Paris, into the family of a silk merchant. From an early age he showed a pronounced talent for mechanics: it is known that at the age of nine Bourdon constructed a small winding device for silk threads, which he used to reel silk from the cocoons of silkworms he had raised himself. Despite his son’s technical abilities, Bourdon’s father intended him for a commercial career and sent him to Nuremberg for two years to study the German language. After returning to Paris, Bourdon initially assisted his father in business matters; however, following his father’s death in 1830, he devoted himself entirely to engineering.

In the early 1830s he gained practical experience as a hired worker, first in the optical workshop of Monsieur Jaeker, and later with M. Calla the elder. Finally, in 1832, at the age of twenty-four, Bourdon founded his own workshop for scientific instruments, initially located at 12 Rue de Vendôme. Already in its first year, Bourdon attracted the attention of the Société d’Encouragement pour l’Industrie Nationale by presenting a model steam engine with a glass cylinder, for which he was awarded a silver medal. In the following years he produced approximately two hundred instructional models of steam engines for educational institutions in France and abroad.

His business developed successfully: having accumulated sufficient capital, in 1835 Bourdon opened larger mechanical workshops at 74 Rue du Faubourg-du-Temple, initially renting the premises and later acquiring them. The enterprise prospered, which was a rarity among inventors of the period. Even before the wide dissemination of his famous pressure gauge, Bourdon proposed original machines; in 1839, for example, he created one of the earliest portable steam engines (a “locomobile”).

The Bourdon Tube

Bourdon’s principal contribution to industry was the creation of a metallic pressure gauge based on a flexible, curved tube—an element now known as the Bourdon tube. In the 1840s Bourdon was engaged in manufacturing models of steam engines and compressors and sought a method for measuring pressure in boilers and receivers without relying on cumbersome and fragile mercury manometers. According to a well-known apocryphal account, during tests of a steam engine model in Bourdon’s workshop, a lead serpentine condenser tube was accidentally crushed. An urgent repair was required, and Bourdon attempted to straighten the dents by forcing water into the tube under high pressure. To the astonishment of the mechanic, the flattened lead tube began to straighten as the internal pressure increased. This observation suggested to Bourdon the possibility of using the elastic deformation of a hollow tube to measure pressure.

It is known, however, that at approximately the same time the Prussian railway engineer Schinz was already employing a curved tube of oval cross-section in his pressure gauges. Is it possible that two scientists independently arrived at the same measuring element? Undoubtedly. Nevertheless, the confidence placed in Bourdon was later undermined by a related episode concerning the mercury-free barometer, which he publicly presented through the press as his own invention, temporarily appropriating the credit for the discovery from the true inventor of the metallic barometer, Lucien Vidie. This matter will be addressed below. It should be emphasized here that Bourdon was unquestionably a brilliant individual and a passionate engineer, who combined technical ingenuity with a pronounced entrepreneurial strategy, actively patenting and commercializing his developments.

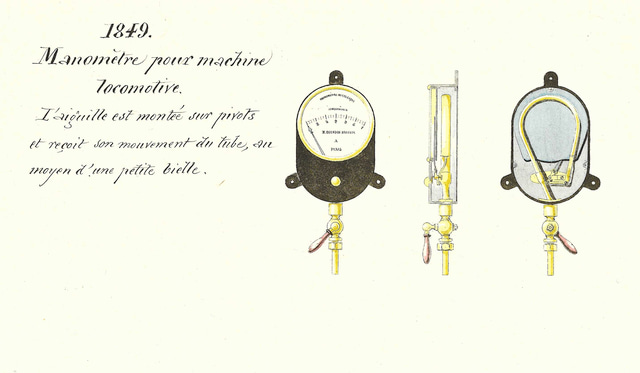

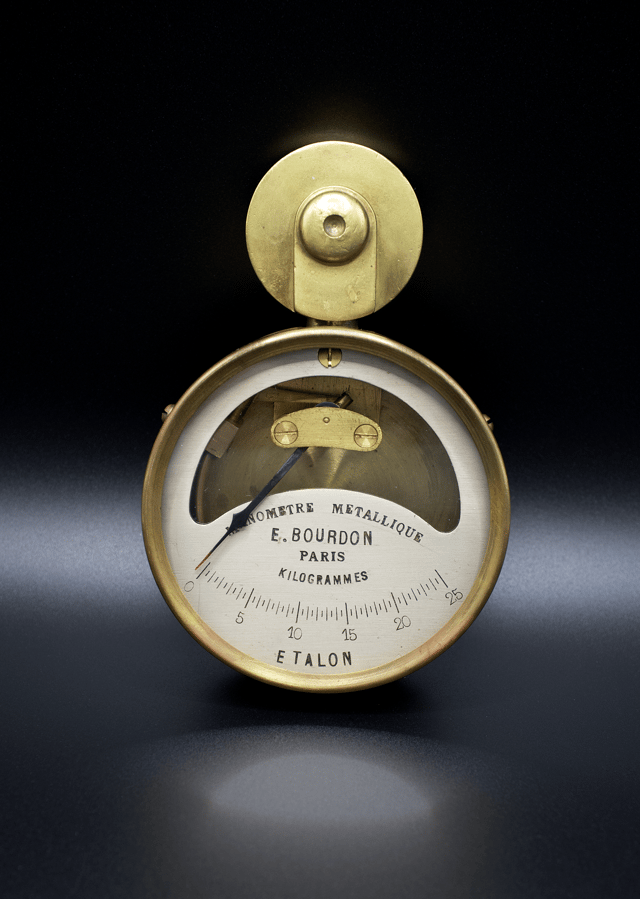

Bourdon quickly developed the first prototype of a metallic pressure gauge in which a curved metal tube of oval cross-section bends and partially straightens as pressure increases. By connecting the free end of such a tube to a simple pointer mechanism, it became possible to display the degree of deformation—and therefore the pressure—on a circular dial. On June 18, 1849, he patented his instrument in Paris. Notably, the 1849 patent covered not only a pressure gauge for measuring gas and liquid pressure, but also a variant of a barometer employing the same elastic tube principle to measure atmospheric pressure.

The new Bourdon manometer immediately attracted the attention of industrialists: it was a compact, liquid-free pressure indicator suitable for integration into machinery. The importance of this invention was acknowledged both by contemporaries and by later generations. In 1884, the French engineer Henri Tresca wrote that Bourdon’s metallic pressure gauge was one of the most fruitful mechanical innovations of the nineteenth century. Indeed, the Bourdon principle proved extraordinarily successful: the flexible tube as a pressure-sensing element is still used today in the majority of mechanical pressure gauges worldwide.

Partnership with Félix Richard and Early Success

As a gifted inventor, Bourdon understood the importance of collaboration for bringing his instrument to market. Almost immediately after patenting it in 1849, he transferred licenses for the production of metallic pressure gauges to the Parisian workshop of Félix Richard (1809–1876). Richard was a well-known instrument maker, specializing in barometers and meteorological recording instruments, and he provided invaluable assistance in establishing serial production of the new device.

Under the partnership Bourdon & Richard, the manufacture of pressure gauges and barometers with elastic tubes began; the dials of these instruments bore both names, Bourdon as inventor and Richard as manufacturer. Already in 1849, at the Paris industrial exhibition, Bourdon’s manometer caused a sensation and received a large gold medal. Two years later, the invention was presented at the Great Exhibition in London (1851), where it was awarded the Council Medal, the highest distinction of the jury. At the same exhibition, Lucien Vidie’s aneroid barometer was also honored, and it was from this moment that the rivalry between the two inventors began. International recognition was further consolidated by France’s highest state honor: in 1851 Bourdon was appointed a Knight of the Legion of Honour.

The collaboration between Bourdon and Richard proved long-lasting and productive. Over time, the rights to the invention fully passed to Richard’s workshop (Bourdon later sold his patent), although Bourdon himself continued to work closely on improvements. After Félix Richard’s death, his sons Jules and Max Richard continued the business, founding the firm Richard Frères in 1882. They became legendary manufacturers of recording instruments (barographs) and other scientific devices, further developing technologies that were based, in part, on Bourdon’s inventions. Instruments bearing the Bourdon & Richard signature were produced until the end of the nineteenth century and are today considered collectible rarities, valued for both craftsmanship and historical significance.

Bourdon Manometers and Their Fields of Application

Bourdon’s metallic pressure gauge quickly found extremely wide application in mid-nineteenth-century industry. Its operating principle consisted in connecting one end of a curved elastic tube to the measured reservoir (for example, a steam boiler), while the other end was hermetically sealed and linked to a pointer mechanism. As pressure increased, the tube tended to straighten, and this movement was transmitted through gearing to the dial indicator.

Unlike earlier U-shaped mercury manometers, the new instrument contained no liquids and was therefore far more convenient: compact, robust, and capable of measuring high pressures. By the 1850s, Bourdon manometers were being installed on steam engines, boilers, locomotives, and marine steam engines, providing engineers with a clear and reliable means of pressure control. The measurable range was extremely broad—from low pressures to hundreds of atmospheres, depending on the material and geometry of the tube. According to specialists, Bourdon’s instrument was suitable for measurements from one atmosphere to hundreds of megapascals, making it a universal indicator for steam, water, gas, and other media.

The invention soon spread beyond France. In the United States, a young engineer named Edward Ashcroft was so impressed by the new pressure gauge that in 1852 he acquired from Bourdon the exclusive patent rights to manufacture the Bourdon tube in America. By the late 1850s, analogous instruments were being mass-produced in the United States under the Ashcroft Gauge brand, playing an important role in the expansion of steam technology across the Atlantic. Thus, the invention of the Parisian instrument maker achieved global dissemination, and Bourdon himself amassed considerable wealth from the production of pressure gauges, which constituted a substantial portion of his fortune.

Bourdon Barometers and the Legal Dispute

Almost simultaneously with his work on manometers, Bourdon proposed applying his tube to the measurement of atmospheric pressure, referring to such an instrument as a “metallic barometer”. Its operating principle resembles that of Lucien Vidie’s classical aneroid barometer, except that instead of a corrugated capsule, it employs a flattened metallic tubular contour. The tube is hermetically sealed and partially evacuated, so that changes in external pressure cause elastic deformation. Through a system of levers and sector gears analogous to that used in manometers, the tube’s motion is transmitted to a pointer indicating atmospheric pressure on a circular scale.

Here lies the essence of Bourdon’s claimed construction. As early as 1844, Lucien Vidie had obtained a patent in France—and a year later in England—describing in detail the operating principle of his invention, the aneroid barometer. The principle consisted in “subjecting atmospheric pressure to the greater or lesser compression of the walls of a hermetically sealed vessel capable of resisting it either by itself or with the aid of springs, and multiplying the effect by means of a mechanism.” The barometer relied on oscillatory movements of an elastic body under atmospheric pressure, with a vacuum inside; the vessel was given a form that produced unequal resistances, and it was connected to a mechanism that amplified and displayed the movement. Thus, the inequality of resistance constituted the essence of Vidie’s patent. Among the possible forms, he favored the cylindrical one because it produced a stronger effect. The patent did not specify a single geometry, thereby covering any metallic hollow form with a vacuum inside.

Several years later, Bourdon’s patent described a barometer consisting of a flattened metallic tube from which air had been completely removed. In this state, the tube possessed the ability to expand: its ends separated when atmospheric pressure decreased and moved together when pressure increased, producing contraction. A lever was attached to the end of the tube through a suitable mechanism connected to an indicator or pointer moving over a graduated scale.

Vidie, of course, understood and stated that his invention could also be used as a manometer (as was indeed the case, for example, in devices for measuring arterial blood pressure). However, its application as a barometer became his principal field of activity. Bourdon, by contrast, likely began with the manufacture of manometers in order to avoid Vidie’s barometer patents. Recognizing the prospects of compact barometers, he soon turned to their production as well, infringing Vidie’s patents while asserting that his tube constituted an independent type of barometer.

The court record speaks for itself:

“Considering that Bourdon, by wrongly presenting himself as the inventor of the metallic barometer, caused Vidie significant moral and material damage; and that, moreover, Bourdon and Richard, by manufacturing and distributing up to the day of seizure 9,400 counterfeit barometers, further aggravated this damage, for which they are required to pay compensation estimated at 25,000 francs;

On these grounds, the Court rules that the barometers manufactured by Richard under the name of metallic barometers constitute counterfeit aneroid barometers, the exclusive right to manufacture which belongs to Vidie;

Consequently, it declares lawful and valid the seizure carried out in Richard’s workshops and orders that all tools and parts listed in the seizure report be handed over to Vidie;

It also condemns Bourdon and Richard, jointly and severally, by all means provided by law, including personal imprisonment, to pay Vidie the sum of 25,000 francs as compensation for the damage caused, setting a two-year term of imprisonment in the event of non-payment;

It condemns Bourdon and Richard to pay all court costs.”

Without in any way diminishing Bourdon’s achievements, it should be noted that this episode represents a lesser-known but well-documented part of the history of the aneroid barometer in France—one that is seldom described, for understandable reasons, in sources connected with the legacy of an unquestionably talented engineer. Bourdon invested considerable effort during the legal proceedings to preserve his patent rights; these actions are also not particularly flattering and are not detailed here. But, damn it, how beautiful his tubes are in barometers and manometers.

Later Years, Legacy, and Succession

By the early 1870s, Eugène Bourdon was already a recognized inventor and a wealthy entrepreneur. In 1872, after nearly forty years of work, he withdrew from active management of the factory, transferring control to his eldest son. Bourdon did not abandon his scientific interests, however: in his remaining years he realized a number of original ideas and continued collaborating with colleagues. In a special museum at his home, he assembled a collection of all the instruments he had created, from childhood devices to his latest developments.

Among the instruments he demonstrated to visitors were a recording barograph with a spiral tube (which recorded pressure changes with a pen on a rotating drum), a thermograph with a helical tube filled with a liquid responsive to temperature, and a curious “atmospheric clock,” in which the main driving spring was a curved manometric tube whose tension varied with atmospheric pressure. These experiments illustrated the broad potential of the Bourdon tube principle.

In November 1884, at the age of seventy-six, the indefatigable inventor was testing a new anemometer of his own design based on the Venturi effect (measuring wind force through pressure reduction in a constricted channel). During one such experiment, Bourdon was traveling in a special carriage behind a locomotive when an accident occurred: he fell from the moving train and suffered a severe cranial injury. A few days later, on September 29, 1884, Eugène Bourdon died in Paris as a result of his injuries. He was buried at Père Lachaise Cemetery, Division 14, where his grave survives to this day.

Bourdon left behind not only a monument to technical thought, but also the continuation of his enterprise. He bequeathed to his children a prosperous business and a celebrated name. His descendants continued to collaborate with the Richard family, with the Richards retaining licenses and production of many Bourdon instruments. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the company founded by Bourdon continued operating under various names; it is noted, in particular, that it eventually became known as Bourdon-Sédémé (from Sédémé—Société Européenne des Appareils de Mesure). The inventor’s name lived on in subsequent generations of instrument makers: for example, Bourdon’s great-nephew Léon Bourdon was also engaged in the manufacture of manometers and other pressure-measuring devices in the early twentieth century, and such instruments were mentioned in contemporary press as “Bourdon manometers.” As for long-standing partners, the firm Richard Frères achieved worldwide renown for its aneroid barometers, recording instruments, and other precision devices, laying the foundations of the French meteorological instrument-making tradition.

Thus, the inventions of Charles Eugène Bourdon continued to live on through his successors and followers. The Bourdon tube he created has permanently entered the history of technology: today its principle is used in virtually all mechanical pressure gauges, from household pumps to the most complex industrial systems. And the name “Bourdon” can still be found on instrument dials; more than a century after the inventor’s death, the Bourdon brand remains synonymous worldwide with reliable pressure measurement.