Background: Guilbert & Cie and Aneroid Barometers

In the second half of the nineteenth century, the first French manufacturers of aneroid barometers—liquid-free pressure-measuring instruments invented by Lucien Vidie (patent of 1844)—began to appear. After the expiration of Vidie’s patent in 1859, French firms rapidly adopted and developed the production of these instruments. One of them was the Parisian company Guilbert & Cie, which specialised specifically in aneroid barometers. The firm became well known for its distinctive trademark: a leather belt motif with the initials “G & C” at its centre. Guilbert barometers were exported, for example, to the British market, where there was strong demand for such instruments during the Victorian period.

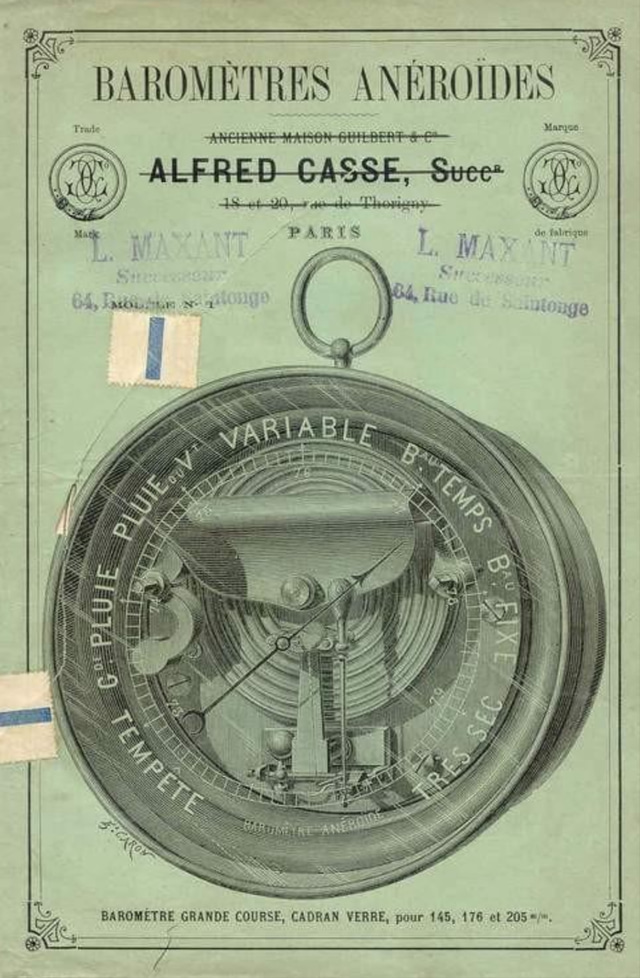

Very little documentation survives concerning the founding of Guilbert & Cie. It is known, however, that around 1890 the firm was acquired by the instrument maker Alfred Casse. Alfred Casse would later become a key figure in the history of another prominent firm, Dubois et Casse. As for the surname Dubois, it had been associated with Parisian instrument making since the eighteenth century: for example, David Frédérique Dubois is recorded as a master instrument maker from 1780, operating a shop on Rue Saint-Honoré from 1782 and later on Rue du Roule from 1783. Thus, by the mid-nineteenth century, Paris already possessed a well-established tradition of producing “philosophical instruments” (scientific instruments), particularly barometers, upon which subsequent generations of entrepreneurs were able to build.

The Founding of Dubois & Casse

The partnership Dubois et Casse was established in Paris around 1860. It was founded by a Parisian mechanic named Dubois and Casse, of Swiss origin according to contemporary press reports, who became his business partner. By 1861, the firm was operating at 17, Rue Grand-Saint-Michel, Paris, as documented in patent archives. On 27 August 1861, Dubois & Casse filed their first invention patent (No. 50959, granted for 15 years), followed by a second patent on 2 November 1863 (No. 60674, also for 15 years). Both patents appear to have concerned improvements to the construction of aneroid barometers.

This period coincided with intense competition among inventors. In 1860, the firm Naudet (PHBN) patented an “improved barometer,” forcing Dubois & Casse to modify their own design in order to market their instruments in France. Nevertheless, Dubois & Casse became one of the first firms in Paris to establish industrial-scale production of aneroid barometers after Vidie. By the early 1860s, Dubois et Casse had clearly established itself as a new manufacturer of scientific and meteorological instruments.

Products and Achievements of the Firm

The principal products of Dubois & Casse were aneroid barometers in various forms, ranging from wall-mounted instruments to portable altimetric barometers intended for travellers. Surviving examples indicate that the firm used a proprietary logo: a stylised anchor enclosed within a “D C” monogram. In addition to barometers, the company manufactured manometers (pressure gauges) for technical applications. In the catalogue of a World Exhibition, its exhibits are listed under the heading “Manomètres”. It is also known that at least one Dubois & Casse manometer was donated by the firm itself to an educational collection, most likely the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers.

The company’s instruments were also mentioned in the scientific and popular technical press of the period. For example, its portable barometers were cited in connection with geographical expeditions—to mountains, deserts, and other remote regions—although detailed references still require further research.

Dubois & Casse quickly acquired an excellent reputation. Its instruments were exhibited internationally and received awards. Key milestones include:

*1867, Paris Universal Exhibition: Dubois & Casse barometers attracted the attention of Emperor Napoleon III, who is known to have purchased one of the firm’s barometers at the 1867 Exhibition. The company likely received a medal at this exhibition; official catalogues note that Dubois & Casse were among the awarded exhibitors. *1878, Paris Universal Exhibition: The firm exhibited a manometer with a corrugated (folded) tube of its own design, for which it was again recognised by the International Jury. This development demonstrates the company’s contribution to advances in measuring instruments, as the elastic corrugated tube follows principles related to Vidie’s aneroid capsules. *Technical publications: Drawings and descriptions of Dubois & Casse scientific instruments appeared in French technical journals. The official catalogue of awarded exhibitors explicitly lists “dessins d’appareils de physique Dubois et Casse”—that is, technical drawings of the firm’s instruments submitted for evaluation. This indicates that, beyond finished products, the company also offered innovative design solutions in the field of scientific instrumentation.

Thus, during the 1860s–1880s, Dubois & Casse produced high-quality barometers and related instruments, gaining recognition both in France and internationally.

The End of the Nineteenth Century: Evolution and Mergers

By the late 1880s, the founding generation appears to have withdrawn from active business. Alfred Casse, who remained the central figure, expanded his operations by acquiring competitors. Around 1890, he purchased Guilbert & Cie, incorporating its aneroid barometer production into his own enterprise. It was likely at this time—circa 1890—that the original Dubois & Casse brand ceased to exist. The next stage was taken up by Léon Maxant, who became associated with the firm Guilbert—A. Casse & Cie.

This continuity was reflected even in symbolism: Maxant’s new logo—an anchor combined with initials—was a clear modification of the Dubois & Casse emblem.

Successor: Léon Maxant and the Subsequent History

Léon-Charles Maxant (1856–1936) was a French watchmaker and instrument manufacturer destined to continue the line initiated by Dubois & Casse. He began his career in 1879 as a watchmaker, later shifting his focus to precision measuring instruments. In 1887, he acquired the Parisian firm Desbordes (founded in 1824), which specialised in physical, optical, and navigational instruments.

By consolidating these resources, Léon Maxant established the company “Instruments de Précision – Léon Maxant.” The firm produced a broad range of pressure-related instruments: barometers, manometers, barographs, aerometers, dynamometers, steam safety devices, and more.

The acquisition of Dubois & Casse assets in 1895–1896 enabled Maxant to reach a new level of production and prestige. By inheriting the expertise and technical groundwork of his predecessors, L. Maxant strengthened its position as one of the leading French manufacturers of precision instruments in the early twentieth century. Maxant maintained particularly close ties with the French Navy, supplying marine barometers and other nautical instruments; this relationship earned him the right to incorporate an anchor into his trademark.

In 1905, Léon Maxant completed another major consolidation by acquiring the historic Maison Redier, effectively unifying much of Parisian barometer production. During the 1920s, the firm operated under the name “Instruments de Précision et de Contrôle, Léon Maxant, Successeur”, located at 38–40 Rue Belgrand, Paris. After Léon Maxant’s death in 1936, the business was continued by his sons—Léon-Louis, Lucien, and Jean—who preserved the family enterprise until the mid-twentieth century.

Conclusion

The company Dubois & Casse, founded as a partnership in the 1860s and dissolved in the 1890s, left a significant mark on the history of scientific instrument making. Precise dates of its development—from foundation to merger—are documented in patent records and exhibition reports. Instruments bearing the “Dubois & Casse” signature are now highly valued by collectors, and the succession from Guilbert and Dubois to Alfred Casse and ultimately Léon Maxant illustrates the broader process of consolidation within the French instrument-making industry during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Each generation—craftsmen, engineers, and entrepreneurs alike—contributed to the continuous development of scientific and philosophical instruments.