History of the Barometer

The Discovery of Torricelli and the First Barometer

The experiment with mercury, conducted by Evangelista Torricelli in 1644, laid the foundation for the creation of the first barometer. The scientist discovered that the column of mercury in a tube hangs at a certain height, creating a vacuum in the upper part of the tube, which demonstrates atmospheric pressure. This discovery forever changed the understanding of the nature of the atmosphere and vacuum.

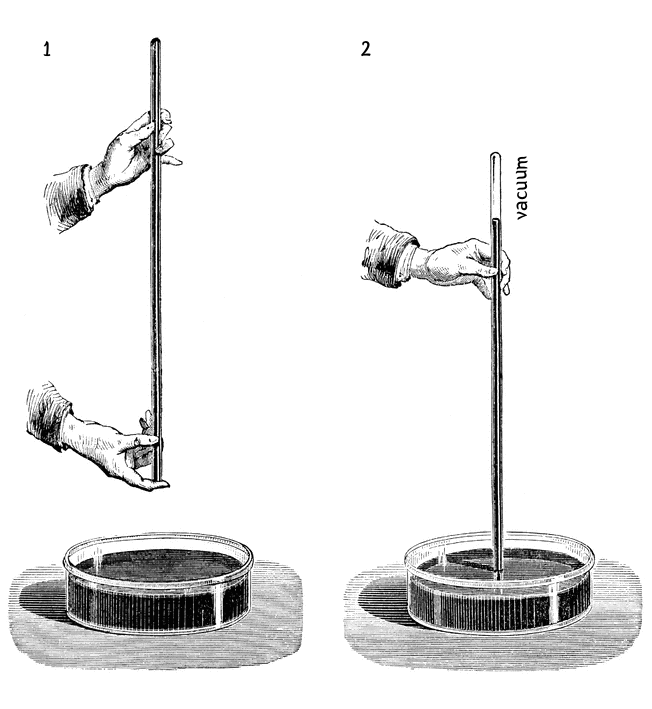

The story of the barometer usually begins with the famous experiment with mercury conducted in 1644 by the Italian physicist and mathematician Evangelista Torricelli. This scientist made such a remarkable discovery that it forever changed our view of the atmosphere and the very concept of a vacuum. Torricelli took a long glass tube filled with mercury and, closing its open end with his finger, inverted the tube and immersed it in a shallow dish also filled with mercury. He then removed his finger, allowing gravity to take effect. As expected, the heavy mercury began to pour into the dish, but suddenly the process stopped — the column of mercury in the tube hung at a height of approximately 760 millimeters from the surface of the mercury in the dish. In the upper part of the tube, above the lowered column of mercury, an empty space formed — a vacuum.

When Torricelli removes the tube and takes away his finger, the column of mercury is balanced by the weight of the air (il peso dell'aria). Atmospheric pressure presses on the surface of the mercury in the dish and is transmitted to the mercury in the tube, pushing it upward. The height of the mercury column in the tube thus becomes a direct measure of atmospheric pressure. Since the space in the upper part of the tube contains no air and is not open to the pressure from outside air, the pressure in the tube from below is balanced by the weight of the mercury in the tube. When air pressure rises, it pushes the mercury up more, causing the column to rise; when the pressure falls, the mercury column lowers. Thus, the vacuum space in the upper part of Torricelli's tube is the main driver of the barometer.

The glass tube that Torricelli used to measure air pressure, later called the Torricellian tube, became the starting point for an instrument whose purpose was to measure the weight of air. The word “barometer,” from the Greek “baros” — weight, heaviness, and “metreo” — to measure, literally means this. The weight or heaviness of air is the force with which air presses on the Earth's surface, equal to about 10 tons per square meter at sea level under standard atmospheric pressure (100 kilopascals). That is, an air column with a base area of 1 square meter and a height of 100 kilometers to the edge of space weighs about 10 tons. Air pressure, in turn, is the force exerted on a unit area due to the weight of the air column above it (equivalent to 760 millimeters of mercury under the same conditions). Simply put, air pressure is the result of the weight of this air column.

The Experiment of Pierre Petit and Pascal

The first experiment outside of Italy was conducted by the Frenchman Pierre Petit in 1646. Through a friend, he informed Blaise Pascal of Torricelli's discovery, and Pascal, along with Descartes, continued the research, attaching a paper scale to the tube, making the barometer a measuring instrument. Pascal later initiated an experiment in the mountains to prove the change in atmospheric pressure at altitude.

The first Torricellian experiment outside of Italy was conducted in 1646 by the French scientist, physician, and poet Pierre Petit. He learned the details of Torricelli's experiment from his friend Angelo Ricci, to whom Torricelli personally described it in a letter. Inspired by Torricelli's findings, Petit shared the details with his friend and compatriot Blaise Pascal, already a famous mathematician and physicist. On September 23, 1647, Pascal met with Descartes to discuss the significance of Torricelli's experiment and its interpretation. They debated for a long time until Descartes, who interpreted the vacuum as a manifestation of life force, decided to conduct a new experiment. He suggested that Pascal repeat the mercury experiment in the mountains, believing that at higher altitudes, the weight of the air would decrease, which should be reflected in the level of mercury in the tube. Descartes believed that such an experiment would demonstrate the effect of altitude on atmospheric pressure and test the theoretical assumptions about the weight of air.

To allow Pascal to visually document the expected changes during the experiment, the meticulous Descartes did something that forever changed the history of meteorological observation — he attached a paper scale to the glass tube intended for the Torricelli experiment. From that moment on, the history of the barometer as a measuring instrument, not just a scientific experiment, began.

The Experiment on the Summit of Puy-de-Dôme

In 1648, Florin Périer, Pascal's brother-in-law, conducted the famous experiment on the mountain Puy-de-Dôme. By measuring pressure at different altitudes, he confirmed that air pressure decreases with height, thus proving the hypothesis about the weight of air. Unable to conduct the experiment himself in a higher location, Pascal wrote to his brother-in-law, Florin Périer, a French lawyer living in Clermont-Ferrand, asking him to perform a similar experiment.

On September 19, 1648, Périer carefully took measurements at various heights on the summit of Puy-de-Dôme, a mountain near the town. This is known as the Puy-de-Dôme experiment. Périer used two tubes, each with a paper scale attached — now a standard for all experiments — marked with numbers indicating the distance in French inches from the mercury level in the reservoir to its meniscus. Both tubes showed the same reading of 26.35 inch of mercury, which corresponds to approximately 712 millimeters of mercury (the city of Clermont-Ferrand was several hundred meters above sea level). Périer left one tube in the care of the Jesuit Chastel, instructing him to observe it throughout the day, while he climbed to the summit of Puy-de-Dôme, where the mercury column showed a reading of 23⅙ inches (627.12 millimeters of mercury). Upon returning to Clermont-Ferrand, the tube again showed 26 inches and 3.5 lines. Périer immediately reported the results of the experiment to Pascal, who described it in his “Récit de la grande expérience de l'équilibre des liqueurs” (Account of the Great Experiment on the Equilibrium of Liquids).

Robert Boyle's Contribution

Inspired by Torricelli's work, Robert Boyle brought knowledge of the barometer to England and demonstrated that the changes in the height of the mercury column were caused by atmospheric pressure. He was also the first to use the word “barometer” in his scientific writings.

Robert Boyle was a student in Italy at the time when Torricelli was conducting his experiments with mercury. Upon returning to England, Boyle brought with him the details of the experiment and proved that the observed phenomena were caused by air pressure. He demonstrated that sound cannot exist in a vacuum, that air is essential for life and combustion, and that air has constant elasticity. It is not exactly known when the experiment became a device, moving beyond the demonstration of air properties. However, Boyle was the first to use the word “barometer” in his work New Experiments and Observations Touching Cold.

Robert Hooke and the Wheel Barometer

In 1664, Robert Hooke created the “Wheel Barometer,” which allowed for precise measurements of the smallest changes in atmospheric pressure. Hooke's invention, based on a modified siphon tube, was the precursor to the elegant and functional “banjo” barometers.

On August 17, 1664, Robert Hooke, a prominent English natural philosopher, inventor, and assistant to Robert Boyle, invented the “Wheel Barometer.” Hooke aimed to address the problem of accuracy and convenience when taking readings from a barometer. The core of his invention was a modified siphon tube in which even the slightest changes in the mercury column height could be accurately recorded and displayed on a dial, similar to a clock. The genius of Hooke's idea lay in the use of a float placed on the surface of the mercury in the short arm of the siphon. A string was attached to the float and ran to a small wheel, which turned a pointer on the dial. As the mercury column rose or fell, the float moved, driving the wheel. To ensure the smooth operation of the mechanism, Hooke added a counterweight attached to the opposite side of the wheel, balancing the float and preventing sharp fluctuations of the pointer. Hooke's invention became the forerunner of the legendary “banjo” barometers, which in subsequent centuries gained wide popularity due to their graceful case design and functionality.

Hooke was among the first to observe the correlation between weather conditions and changes in the mercury column. His observations showed that a drop in mercury level typically preceded worsening weather, including rain, stronger winds, and even thunderstorms. Conversely, a rise in the mercury column often indicated approaching clear and dry weather. Hooke's conclusions helped lay the foundation for future methods of weather prediction, using the movement of the mercury column as a key indicator of changes in the atmosphere.

Hooke's Two-Liquid and Three-Liquid Barometers

Robert Hooke continued his research, creating a two-liquid barometer in 1668, where oil served as a buffer between mercury and atmospheric pressure. Later, he developed a three-liquid barometer, which further improved the accuracy of measurements.

In 1668, Robert Hooke, continuing his studies on the scaling of barometric readings, invented the “Two-Liquid Barometer,” also known as the “Double Barometer” (Doppelbarometer) or “Counter Barometer” (Contrabarometer). This innovative instrument consisted of two tubes connected in a U-shape. One tube, usually the left one, was filled with mercury and sealed at the top, where a small reservoir served as a cistern for mercury. The other tube, the right one, was open at the top and contained colored oil. At the junction of the two tubes was a small reservoir where the two liquids met but did not mix due to their difference in density.

Unlike traditional siphon barometers and Torricelli's tube, where air pressure directly acted on the mercury column, in the counter barometer, the atmosphere acted through the open tube on the oil, which then influenced the movement of the mercury. Thus, the oil served as a buffer between the mercury and the atmosphere, allowing for a reduced effect of temperature changes. Under atmospheric pressure, the oil column varied widely, while the denser mercury moved within a range of about five centimeters in Torricelli's tube. Significant scaling of the counter barometer was achieved through the difference in the internal cross-section of the tube filled with the indicator liquid and the cross-section of the reservoir.

The distinctive feature of Hooke's counter barometer was that the readings were taken directly from the oil column, with the pressure values on the scale arranged in reverse order, since the movement of the liquid column was “reverse” compared to Torricelli's tube. When atmospheric pressure rose, the oil in the right tube dropped, while the mercury in the left tube rose, and vice versa — when the pressure dropped, the oil rose, and the mercury fell. Thus, the lower values on the scale indicated high pressure, while the upper values indicated low pressure. Hence the name “Counter Barometer.”

The most vulnerable element of counter barometers was the open oil-filled tube. Over time, the oil would inevitably evaporate, become contaminated, and dry out, significantly impairing the device's performance. Acknowledging this problem, the prolific and inventive Robert Hooke, in 1685, proposed an interesting solution — the “Three-Liquid Barometer,” in which the oil column was placed between two mercury columns. This design helped partially address the issues related to oil evaporation and contamination. A quarter-century later, in 1710, the French scientist Nicolas Gauger proposed a new modification — the “Four-Liquid Barometer” or “Folded Barometer.” This device not only improved reliability by reducing the barometer's height by “folding” the tubes with different liquids in a row but also looked aesthetically impressive.

Although the four-liquid barometer was an impressive achievement, it was not the most practical invention. Despite reducing the instrument's height, the design became more fragile due to the increased number of glass tubes, and its transportation was complicated by the high risk of liquid mixing. Nevertheless, the folded barometer became a logical and striking culmination of the evolution of two-liquid barometers initiated by Robert Hooke.

Diagonal Barometers and the Development of Trade

As barometers advanced, they became commodities in London and Paris. “Diagonal barometers,” invented in the late 17th century, became popular due to their high accuracy and elegant design. They took up more space, but this was compensated by increased precision.

In 1670, the barometer became a trade commodity in London and Paris, and weather observation turned into a popular activity among gentlemen. Initially, barometers were expensive devices accessible only to aristocrats, but by the 18th century, with growing prosperity and the development of scientific instrument production, they became available to middle-class households.

One of the most notable examples of the next phase of barometer refinement was the “diagonal barometer,” also known as the “angled barometer,” and in England, referred to as “Sign Post” or “Yard Arm.” This innovative device was simultaneously invented by Sir Samuel Morland, a knight and baronet, around 1680 in Britain, and by the physician Bernardino Ramazzini in Italy in 1694-1695. They discovered that if the Torricellian tube was bent just below the lowest point where mercury could drop (about 27.5 inches or 70 centimeters above the cistern), and then extended at an angle, mercury would travel diagonally over a much greater distance than in a vertical tube. The degree of this movement depended on the angle of the glass tube, which determined how far the mercury would move with changes in pressure. This increased sensitivity and precision in measurements, significantly enlarging the scale, making atmospheric pressure fluctuations more noticeable to the observer.

Due to its specific design, diagonal barometers took up more width compared to other weather instruments. However, this fact was ingeniously exploited: the barometers were built into frames around mirrors. As a result, this approach produced not only an elegant but also a doubly functional piece of furniture.

The popular diagonal barometer shape in England later inspired craftsmen to create even more complex zigzag designs. In these barometers, the glass tube first made a slight bend to the left and then sharply to the right, resembling the angles of a diagonal barometer. One of the prominent craftsmen, Balthazar Knie, a glassblower and one of the leading makers of Scottish barometers, emigrating from southern Germany to Edinburgh, created technically unique angled barometers that became objects of admiration and collecting.

Over time, diagonal barometers grew in size and complexity. “Double” and “triple diagonal barometers” appeared, equipped with two or more tubes bent one below the other. Each tube covered one inch of the scale: the first showed values from 28 to 29 inches, the second — from 29 to 30 inches, and the third — from 30 to 31 inches. These barometers not only impressed with their appearance but also offered a more detailed scale compared to single-tube models.

Johann Bernoulli, the famous mathematician, is credited with inventing another type of diagonal barometer — the “L-shaped” or “rectangular barometer.” This rare device features a tube bent at a 90-degree angle, giving it the appearance of the letter “L.” In 1710, Bernoulli presented his invention to the Paris Academy of Sciences. However, it is known that in 1673, Jean Dominique Cassini, an outstanding engineer and astronomer, installed such a barometer at the Paris Observatory. In the L-shaped barometer, two tubes connected at a right angle were used to enlarge the scale. The vertical tube was wider than the horizontal one and had a small expansion at the top where the mercury rose and fell. Thus, even a slight drop in mercury in the vertical tube caused a noticeable shift in the horizontal section.

The Invention of the Conical Barometer and England's Contribution

Guillaume Amontons developed the conical barometer in 1695, which was highly sensitive to atmospheric pressure changes. England became the center of barometer production, where many of these instruments were made.

The work of another scientist, Guillaume Amontons, significantly influenced the development of the barometer. A description of one of his ingenious devices, the conical barometer, could be found in his 1695 work, Remarques et expériences physiques sur la construction d'une nouvelle clepsydre, sur les baromètres, thermomètres et hygromètres (Remarks and Physical Experiments on the Construction of a New Water Clock, Barometers, Thermometers, and Hygrometers). It consisted of a conical glass tube with the narrow upper end sealed and the wide lower end open. The diameter of the tube gradually increased downward. Since the mercury was supported by air pressure, the tube was narrow enough, and its length depended on the angle forming the cone. Changes in atmospheric pressure caused the mercury in the tube to rise and fall, thus increasing or decreasing its vertical depth. However, unlike the ordinary Torricellian tube with the same diameter throughout, the conical barometer was extremely more sensitive to changes in atmospheric pressure.

England became the epicenter for the development and spread of barometers. It was here that the barometer found widespread use and became an integral part of scientific research and daily life. Great Italian craftsmen came to England to establish their production, and the largest number of these instruments were made there, which played a key role in their history. The genesis of the barometer, its development, and evolution are closely tied to England.

The Development of the Barometric Scale and Units of Measurement

The history of measuring atmospheric pressure is closely tied to the transition to unified measurement systems, including the use of inches of mercury in England. In the 18th century, the use of vernier scales for precise measurements became standard.

England's influence on the development of the barometer is reflected in the units of measurement used on the scale to express atmospheric pressure — inches of mercury. Before the metric system was introduced in France in 1795, the inch, traditionally defined as one-twelfth of a foot, was a universal measure, though its length varied from country to country, complicating the calibration of instruments internationally.

The history of measuring atmospheric pressure is the story of the transition from regional traditional units of measurement to unified systems, which provide greater accuracy and universality. This transformation, beginning in Europe in the early 19th century with the adoption of the metric system, greatly simplified working with measuring instruments and eliminated confusion caused by different inch standards.

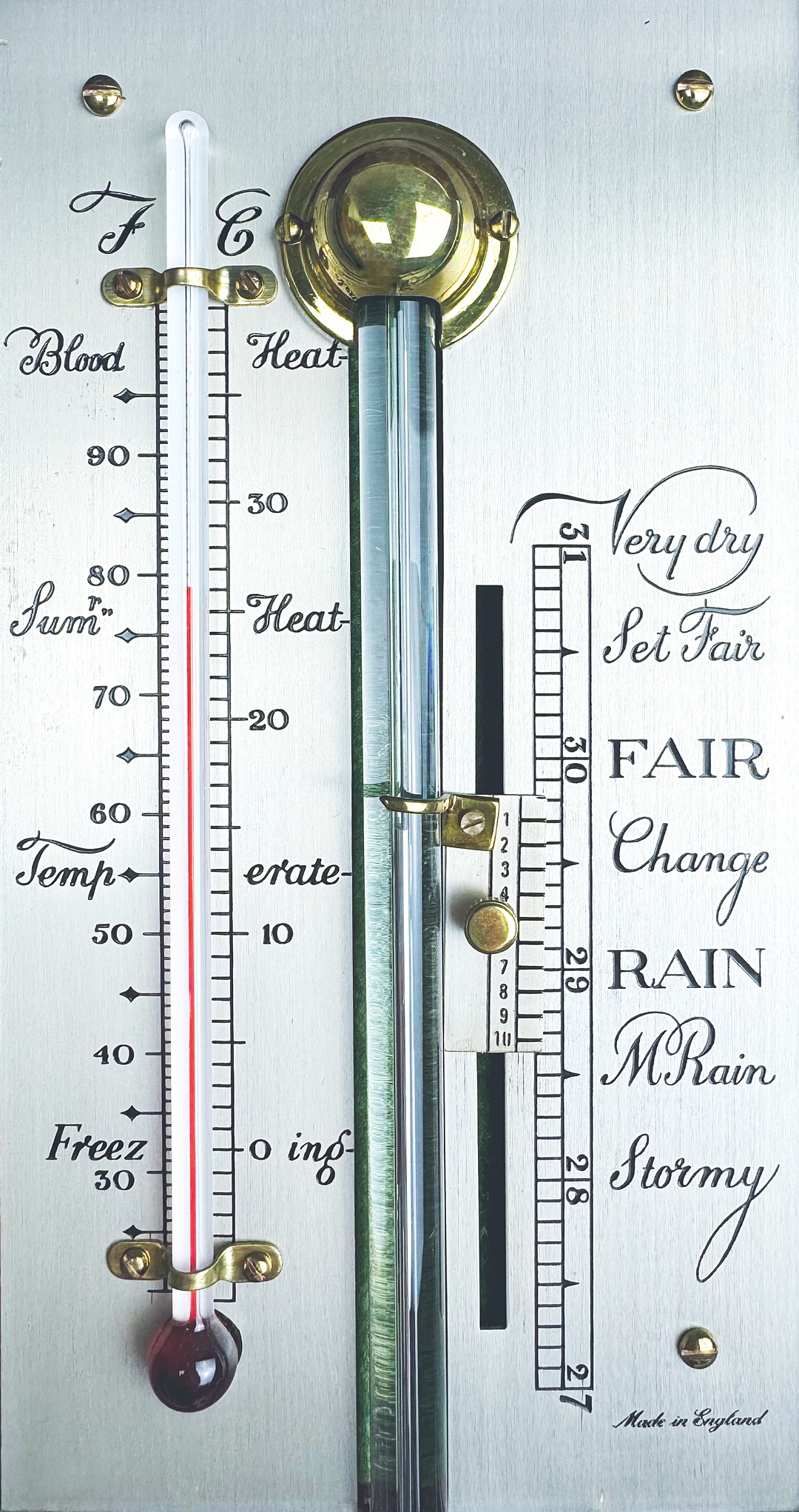

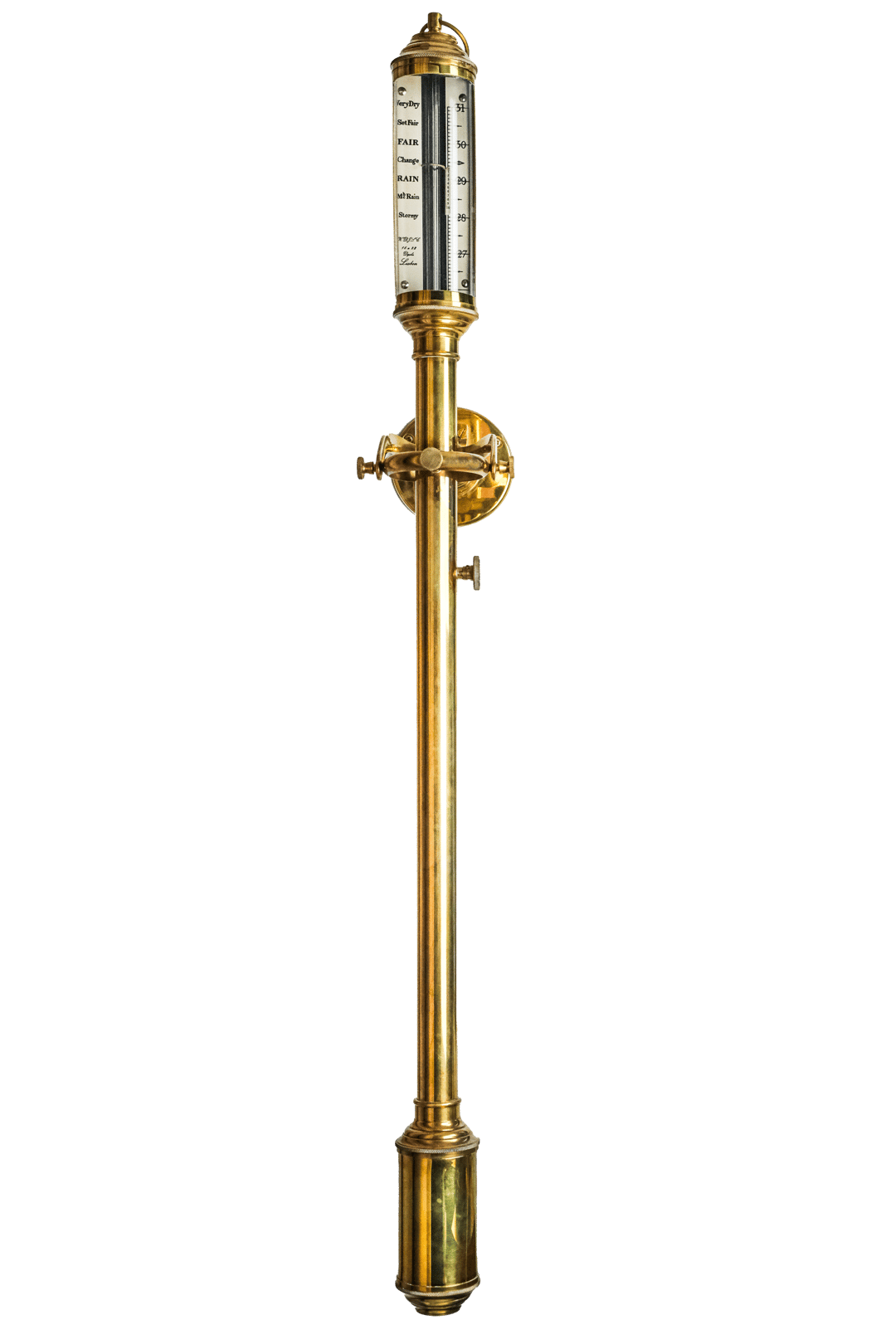

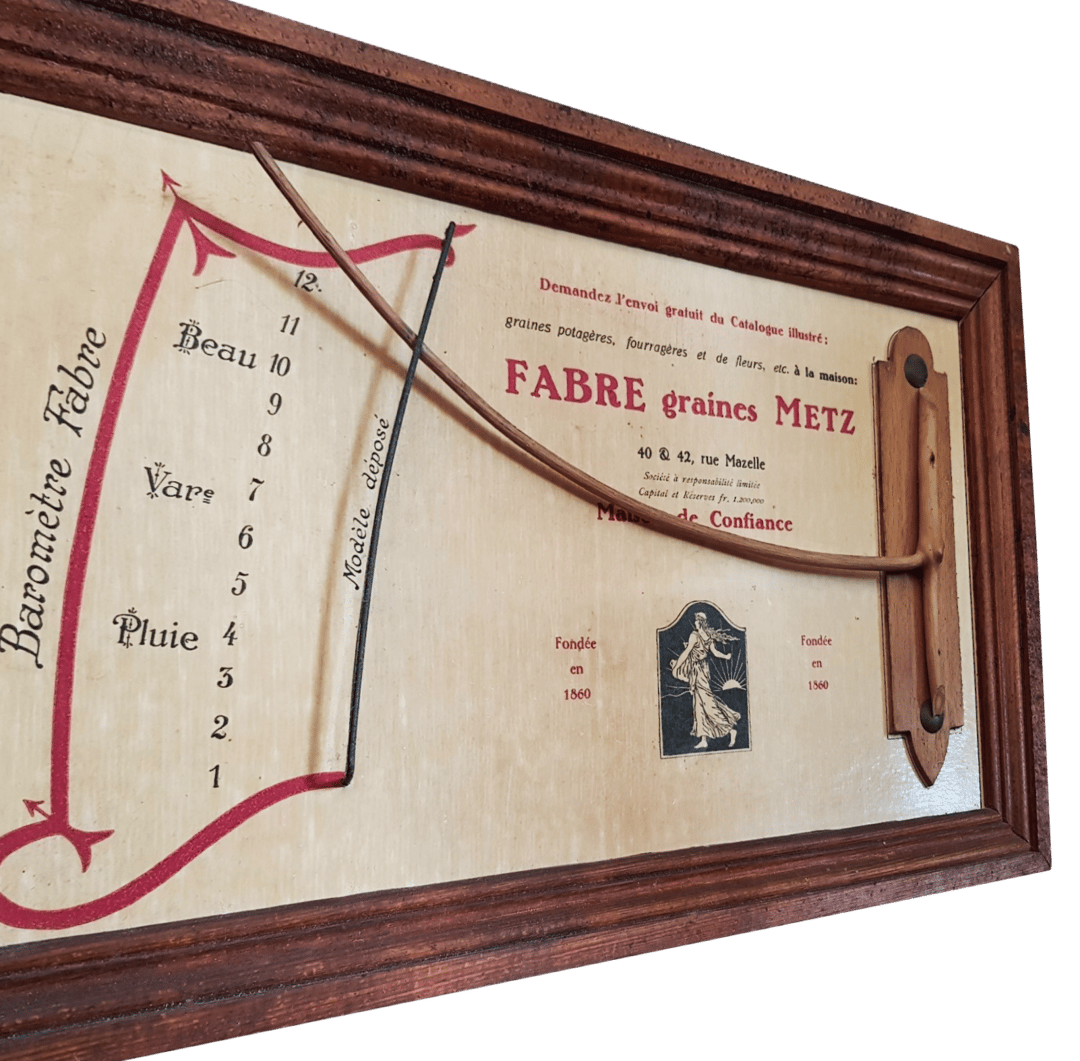

To simplify the understanding of weather trends, in 1688, the Scottish mathematician and engineer George Sinclair completed his barometer, placing six text-based weather indicators on the scale:

“Fair” — Fair

“Changeable” — Changeable

“Rain” — Rain

“Much Rain” — Heavy rain

“Tempest” — Storm

In 1758-1759, Benjamin Martin, a teacher and author of the first English dictionary Lingua Britannica Reformata, proposed a more complete formulation, which became the standard. In 1779, it was quoted by João Jacinto de Magalhães, a Portuguese natural philosopher, who led the creation of meteorological and astronomical instruments for the Madrid court. This formulation included the following indicators:

30½ inches — “Settled Fair” — Settled fair

30 inches — “Fair” — Fair

29½ inches — “Change” — Changeable

29 inches — “Rain” — Rain

28½ inches — “Much Rain” — Heavy rain

28 inches — “Stormy” — Stormy

In the 19th century, it became widely understood that traditional text-based indicators on barometers could be misleading, as they did not always accurately reflect reality. In response to these shortcomings, Admiral Robert FitzRoy, an officer of the British Navy, meteorologist, and Governor of New Zealand, developed his own system of weather indication. FitzRoy added information about wind direction, which influenced weather conditions, as well as detailed textual descriptions of weather changes depending on the movement of the mercury column, based on many years of observation. His system became widely used on various types of barometers. However, despite FitzRoy's improvements, the standard weather indication, which appeared in the late 17th century, continued to be used on almost all barometers, including aneroid ones, after their invention in 1843. These weather indicators were translated into other languages and placed on the dials of barometers produced for different markets. These text-based weather indicators have survived with minor changes even into the 21st century as a tribute to tradition and respect for the history of meteorology.

The Introduction of the Vernier Scale for Increased Accuracy

In the 18th century, barometers began to be fitted with a vernier scale — an auxiliary scale invented by Pierre Vernier, significantly improving the precision of atmospheric pressure measurements.

Starting around 1750, it became common practice to equip barometers with a “vernier” or “nonius,” which significantly increased the accuracy of measurements. The vernier scale was invented around 1630 by Pierre Vernier, a Burgundian mathematician and inventor, and is a secondary scale used on various measuring instruments. This scale allows for a more precise reading of fractions of the main scale divisions, down to decimal places.

Typically, the barometer's main scale is divided into inches and tenths of an inch, while the vernier scale has a length of one and one-tenth inches and is divided into ten equal parts, numbered from one to ten. On barometers with millimeter scales, full millimeters are read off the main scale, while tenths of millimeters are determined using the vernier. Another commonly used name for the vernier is “nonius,” after the Portuguese mathematician Pedro Nunes (lat. Petros Nonius), who proposed a mathematical scale for a similar instrument at the end of the 16th century.

The Torricelli Tube and the Evolution of Cistern Barometers

The Torricelli tube was used in the first cistern barometers, but over time they were made safer by adding covers and using materials like boxwood. This made barometers more reliable and convenient to use.

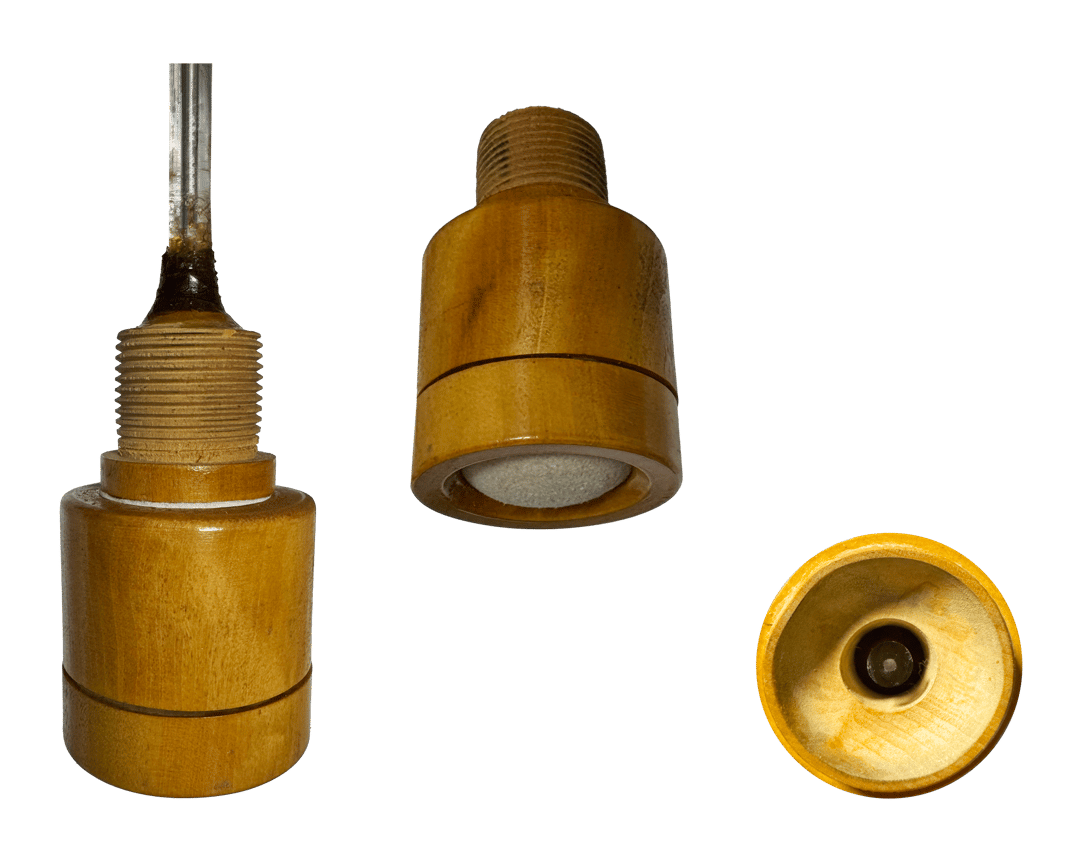

In Torricelli's mercury experiment, the tube had an open cistern — a simple bowl filled with mercury — and the first barometers replicated this design, which is why they were called “Cistern Barometers.” However, due to the high risk of mercury splashing, cisterns were soon made in a closed form, covered with lids that allowed air to interact with the contents. An example of this approach is the cistern made from boxwood. In 1688, the unique properties of certain hardwoods, such as the fine-grained yellow wood Buxus sempervirens and Buxus balearica, known as boxwood, were described. Unlike other types of wood, boxwood allows air to pass through but remains impermeable to mercury vapors, making it indispensable for creating reservoirs in cistern barometers. The history of using boxwood in barometers is an example of how natural materials with unique characteristics can influence the course of scientific inventions, providing a new level of precision and reliability.

In addition to wood, materials such as glass, leather, and various combinations of these were also used in the manufacture of cisterns. In closed cisterns, an adjustment screw was often added, which could press the leather bottom inward, reducing the volume of the reservoir. This allowed for the prevention of mercury movement and minimized the risk of air entering the tube during the transport of the barometer, significantly increasing the reliability and convenience of these instruments.

Stick and Bottle Barometers

Stick and bottle barometers were further developments of cistern instruments. They had different designs but preserved the principle of a mercury column. Siphon tubes were also used in well-known wheel barometers by Hooke.

The next type of barometer, which appeared almost immediately after the cistern ones, was the “Stick Barometer” or “Pediment Barometer.” This type of barometer closely resembles cistern barometers, as the mercury reservoir is also a cistern. The name of this type of barometer is obviously related to the trend of narrowing the instrument's body, giving it a tall, slender form.

The “Cistern Bulb Barometer” or “Bottle Barometer” was the next iteration of the stick barometer. In the lower part of the glass tube of this instrument, there was a bend (a siphon), followed by a small bulb-like expansion (the bottle), where the mercury was housed.

Typically, the siphon barometer is not singled out separately, as the siphon tube is the basis for another well-known device — the “Wheel Barometer” invented by Robert Hooke. Another name for this type of instrument is “Dial Barometers.”

Efforts to Create Accurate Barometers

Standard and reference barometers, such as the “Kew Standard Barometers,” were developed for meteorological laboratories. These devices provided high precision and were used in scientific research.

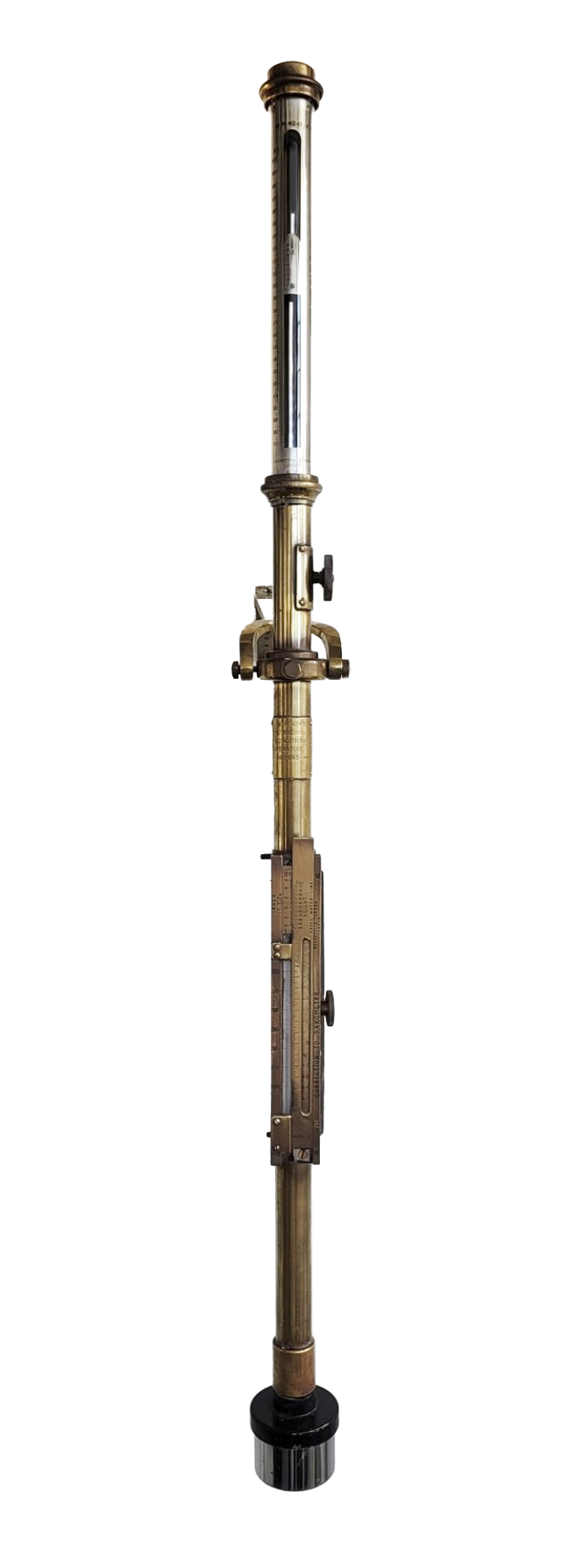

A special place belongs to highly accurate barometers used in meteorological laboratories. These instruments include the “Normal Barometer” (Normalbarometers) in Germany, where it was invented; the “Reference Barometer” (Barométres étalons) or “Standard Barometer” (Standard barometers) in France; as well as the “Kew Standard Barometers” in the United Kingdom. The features of all these instruments are primarily related to the specific and complex construction of the cistern, which minimizes the errors inevitably present in the design of any mercury barometer. Such errors include the effects of temperature and so-called standard errors inherent in the construction of any mercury barometer.

Barometer Components

Barometer plates and dials were not only functional but also aesthetic elements. They were made from various materials such as ivory and enamel plates, creating beautiful and durable instruments.

Every barometer consists of several important elements that not only ensure its functionality but also allow the instrument to be appreciated as a work of art. The plates and dials — the face of the barometer — play a central role in providing precise and understandable weather information. Registration plates for cistern and stick barometers, dials for banjo barometers, and later aneroid barometers, were usually made of silver-plated brass, regular or glossy card (patented by Isaiah Woodcock), opal matte glass, traditional porcelain, enameled metal plates, as well as ivory for more expensive models or paper for more affordable ones. Enameled plates, porcelain, and ivory were widely used in the manufacture of marine barometers, as these materials were resistant to corrosion, making them ideal for use on ships. Carefully selected materials not only gave barometers durability but also made them refined works of art capable of withstanding harsh operating conditions.

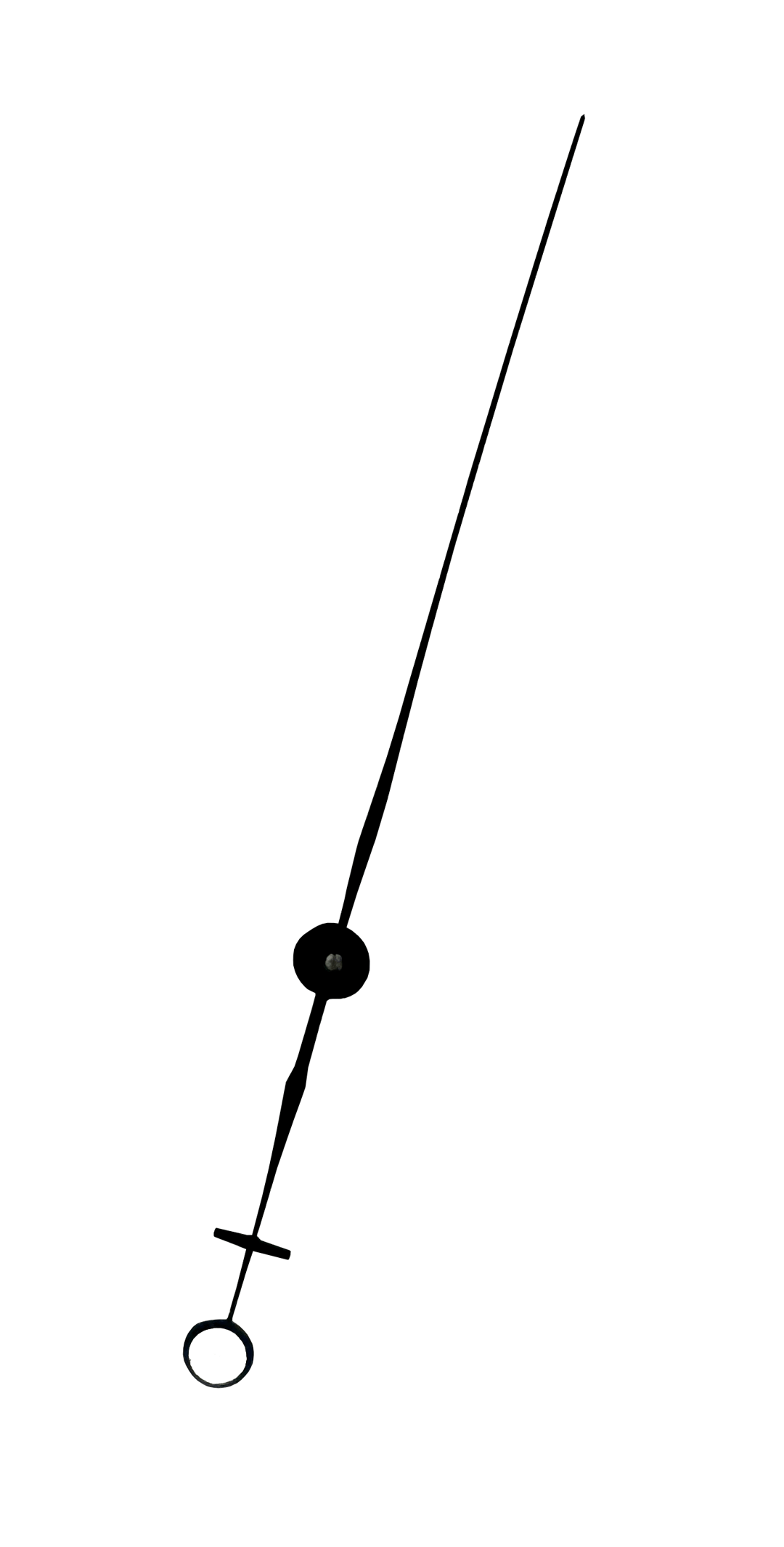

On all dial barometers, steel pointers indicate the current atmospheric pressure, responding to any fluctuations, moving along the scale. Typically, the pointer undergoes bluing — a process of chemical oxidation that creates a protective oxide layer on the surface, giving the pointer an aesthetic appearance with a characteristic blue or bluish tint. This process is also known as browning or bluing. The lower end of the pointer, called the “feather” or “counterweight,” is often adorned with a moon or crescent-shaped element. This not only adds visual appeal but also plays an important role in the construction, helping to balance the pointer and ensure its stable and precise movement along the instrument's scale. On the flat glass that protects the dials of banjo barometers, and on almost all aneroid barometers, there is a second pointer called a marker or trend indicator. Usually made of brass, this pointer can be manually adjusted to record the current pressure value to determine weather trends.

The Contribution of Daniel Quare and Edward Nairne

Daniel Quare proposed an improvement to the barometer by adding a shock-absorbing chamber to prevent the tube from breaking during transport. Edward Nairne developed a marine barometer for use aboard ships, an important step in the development of navigation instruments.

In 1724, Daniel Quare, a prominent English clockmaker and maker of scientific instruments, made a significant improvement to the design of the mercury barometer. To prevent the upper part of the glass tube from being damaged by the weight of the mercury when the barometer was tilted, he added a small spherical chamber located at the top of the tube. This chamber acted as a shock absorber, preventing sudden movements of the mercury and thus reducing the risk of damage to the instrument.

However, it is known that even earlier, in the early 1700s, the London instrument maker Edward Nairne, faced with the problem of sudden mercury fluctuations on board ships that could cause the tube to break, proposed an innovative solution. He narrowed the central section of the tube to one-twentieth of an inch in diameter, significantly reducing the amplitude of mercury movement, preventing it from striking the top of the tube and breaking the glass. This barometer, suspended on gimbals for additional stability, became the first successful marine barometer, tested during James Cook's second voyage. Nairne's innovation not only solved the reliability issues of instruments in marine conditions but also marked an important step in the development of precision instruments for navigation.

However, Daniel Quare's later innovation did not end with the creation of the shock-absorbing chamber. He also proposed the use of a variable-volume cistern, equipped with a screw that pressed against the leather bottom of the cistern. This screw allowed the volume of the cistern to be adjusted by simply turning it, providing a more precise regulation of the mercury level.

Later, this important invention was mistakenly attributed to Jean Nicolas Fortin, a renowned French instrument maker specializing in the creation of scientific tools.

Fortin's Barometer and Mercury Level Adjustment

Jean Nicolas Fortin created an improved barometer with an adjustable cistern, providing high measurement accuracy. This barometer became a standard in scientific research.

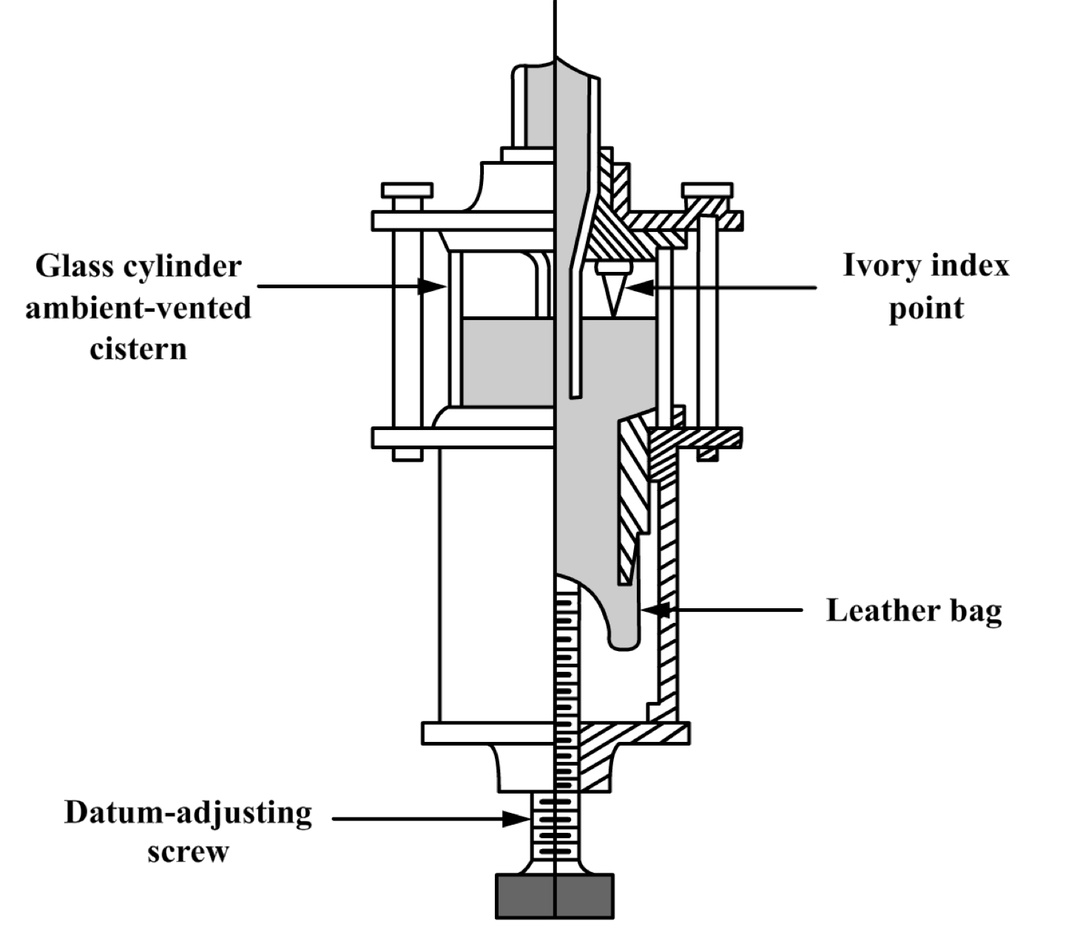

Fortin combined various early innovations and created an improved version of the barometer that became widely known as the “Fortin Barometer.” Its design, which remained virtually unchanged for 150 years, was a model of precision and engineering ingenuity. At the heart of this barometer was the adjustable cistern, consisting of a glass mercury reservoir, a leather bag attached to the bottom of the reservoir, and an ivory point that served as a reference for precisely setting the initial mercury level. The leather bag was connected to an adjustment screw that allowed the volume of the cistern to be changed. Thus, Fortin's cistern enabled fine adjustments of the mercury level before taking measurements, which was critical for the correct calibration of the instrument. The ivory point (ivory index point) served as a reference, allowing the user to accurately set the initial (zero) mercury level. Even small changes in this level could significantly affect the measurement results, so calibration using Fortin's cistern became the standard for precision.

The Marine Barometer of Kew and Gold's Sliding Scale

In 1855, the “Kew Marine Barometer” was developed for use on ships. Ernest Gold added a thermometer to the barometer's scale, allowing for temperature compensation and improved reading accuracy.

In 1853, an international conference was held in Brussels, aimed at developing a systematic plan for meteorological observations at sea. Various recommendations were proposed at the conference, which were adopted by the British government. In response, the government requested the Kew Committee of the British Association to develop a new marine barometer based on the accepted recommendations at the Kew Observatory. Thus, by 1855, the famous “Kew Marine Barometer” was created.

The main element of the barometer — the glass tube — was placed in a narrow copper pipe with an expansion at the bottom to house the cistern. The fixed scale, part of the body, emphasized the practicality and reliability of the instrument. This scale, protected by round glass, had a minimalist design, displaying only atmospheric pressure numbers without any text-based weather indications, highlighting its purely functional purpose. One of the key features of the Kew barometer's mercury tube was the inclusion of special constrictions in certain parts of the tube. These constrictions acted as dampers, effectively limiting sharp changes in mercury levels during the rocking of the ship. This was particularly important in marine voyages, where sudden and violent movements could cause significant inaccuracies in readings. Additionally, an air trap was designed into the lower part of the mercury tube. This trap was meant to capture any small amount of air that might accidentally enter the tube through its open lower end, preventing it from affecting the barometric readings. Any trapped air could later be removed during barometer maintenance, further increasing the reliability of the instrument by preserving its accuracy even in harsh conditions.

An interesting feature of the Kew barometer was an additional device developed by Ernest Gold in 1914, known as the “Gold Slide.” This mechanism consisted of a thermometer integrated into a logarithmic scale, which allowed for the consideration of several factors, such as temperature, altitude, and latitude, all of which could significantly influence the accuracy of barometer readings.

Robert FitzRoy's Contribution to the Development of Barometers

Robert FitzRoy played a key role in advancing barometers for sailors and fishermen, as well as proposing the “Miner's Barometer,” which helped warn against gas explosions in mines.

Thanks to its proven accuracy in practice, Kew barometers were widely used at weather stations, where they were commonly known as “Kew Pattern Station Barometers.” However, their primary application was in the merchant fleet, and the production of these barometers was overseen by the Board of Trade. Meanwhile, a different type of instrument was used on military ships — the “FitzRoy Marine Barometer,” also known as the “Gun Marine Barometer.” This name came from the fact that its glass tube was encased in vulcanized rubber before being placed in a copper tube, significantly reducing the risk of breakage during cannon fire. Extensive tests were conducted on several naval ships under the heaviest artillery fire, and in all circumstances, these barometers withstood even the strongest vibrations. In addition to developing the marine barometer, Robert FitzRoy made a significant contribution to popularizing barometers on land, particularly among the coastal communities of Great Britain. In 1857, recognizing the need to improve the safety of fishermen and residents of coastal towns, he initiated a program to install barometers along the entire British coastline. According to his plan, these devices would provide timely warnings of possible weather changes, which were crucial for people whose work and lives depended on the sea. FitzRoy convinced the company Negretti & Zambra, known for manufacturing precise scientific instruments, to develop and produce a special device — the “Sea Coast Barometer,” which also became known as the “Fisheries Barometer.” These barometers were installed in fishing villages and coastal settlements across the country with the active support of the Admiralty. Thanks to this initiative, local residents could monitor atmospheric pressure independently, allowing them to better predict weather changes and reduce the risks associated with sudden storms and adverse weather conditions.

Miner's Barometers

In 1864, the company Negretti & Zambra developed a miner's barometer to warn against sudden pressure changes that could lead to gas explosions in mines. This device became a mandatory safety measure in the mining industry.

In 1864, Negretti & Zambra developed the “Miner's Barometer,” specifically designed for use in mines. This instrument became an essential safety tool for miners, especially after the British Parliament passed a special act in 1872, making barometers mandatory in the mining industry. By that time, it was well known that sudden drops in air pressure in mines often preceded dangerous gas accumulations, which could lead to explosions. Therefore, miner's barometers played a vital role, providing timely warnings of potential threats and saving the lives of those working in the harsh and hazardous conditions underground.

Aneroid Barometers and Their Spread

With the invention of the aneroid barometer by Lucien Vidie in 1844, a new era of measuring instruments began. Aneroid barometers did not require mercury and were convenient to use.

The transition from mercury barometers to aneroid barometers marked a key moment in barometer history. Although mercury barometers continued to play a crucial role in scientific research, their drawbacks — size, fragility, the danger of mercury spills and its toxic effects, as well as the complexity of manufacturing these instruments — stimulated the search for alternative solutions. This need led to the creation of the aneroid barometer, which became a major step forward due to its ability to provide reliable readings without using mercury.

Two centuries had passed since Torricelli's famous experiment, which began the study of atmospheric pressure. In 1844, Lucien Vidie, a French physicist, invented the first mercury-free barometer, based on his groundbreaking creation — the aneroid sensitive element, later named after him: the Vidie capsule. The Vidie capsule is a small metallic chamber with corrugated walls, from which air is partially evacuated. Lucien Vidie's patented aneroid chamber was a hermetically sealed metal box that deformed under the influence of atmospheric pressure. Inside this capsule were springs that transferred the deformations to the barometer's pointer via a system of levers, providing reciprocating motion. This system, consisting of levers, springs, and axles, allowed for the precise transmission of the capsule's movements to the pointer, displaying the current pressure.

Over time, the barometer's design underwent significant changes. In the next iteration, the internal springs of the capsules were replaced by an external coil spring, which increased sensitivity and measurement accuracy, as the coil spring was prone to twisting during compression. Later, the external spring was replaced with a flat leaf spring, resulting in a more stable and reliable mechanism. In 1859, the patent on Lucien Vidie's invention expired, opening the door for mass production of aneroid barometers based on his mechanism. Despite Vidie's attempts to extend his patent, he was unsuccessful. As a result, a number of British and French manufacturers, including the leading companies of the time, began producing and selling barometers widely using the Vidie mechanism.

Miniature Aneroid Barometers

Negretti & Zambra developed miniature pocket aneroid barometers, revolutionizing the field of measuring instruments. These devices became essential tools in various fields.

At the suggestion of Admiral Robert FitzRoy, Negretti & Zambra began working on the development of a pocket barometer that would finally solve the issue of portability for this important instrument. By 1861, after extensive research, the company introduced a barometer with a diameter of just 46 millimeters, resembling a pocket watch in shape and size. This miniature barometer became a true technological breakthrough, opening new possibilities for using barometers in the field. The grand wooden cases and long mercury tubes gave way to graceful pocket aneroid barometers. Their invention revolutionized various fields, allowing people to carry a barometer in their pocket.

Aneroid Mechanisms: The Vidie mechanism and the conventional continental cantilever type movement

Aneroid barometers, invented by Lucien Vidie, used a metal capsule that deformed under air pressure. Later, the conventional continental cantilever type movement, based on a rack and pinion system, was developed, improving the accuracy and stability of measurements.

Friction and slack in the joints of the levers and linkages in the aneroid mechanism, along with an imperfect balance between various parts, caused constant errors in the readings of early aneroid barometers. Some lever joints were too tight, which led to the pointer sticking and prevented it from moving smoothly. This led to changes in the design and the abandonment of numerous levers.

The result of gradual improvements and adaptations made by various European manufacturers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was the introduction of the rack-and-pinion mechanism. This mechanism converts rotational movement into linear motion, allowing more precise transmission of the capsule's expansion and contraction to the pointer. In the rack-and-pinion system, there is no external spring, and atmospheric pressure is balanced solely by the elasticity of the capsule itself. As the capsule deforms, the gear (pinion) rotates, causing the rack to move linearly, which, in turn, moves the barometer's pointer. This mechanism became the foundation of the so-called conventional continental cantilever type movement, which ensured the smooth and precise conversion of the capsule's deformation into pointer movement, improving measurement accuracy.

Self-Registering Barometers

Self-registering barometers automated the recording of atmospheric pressure readings.

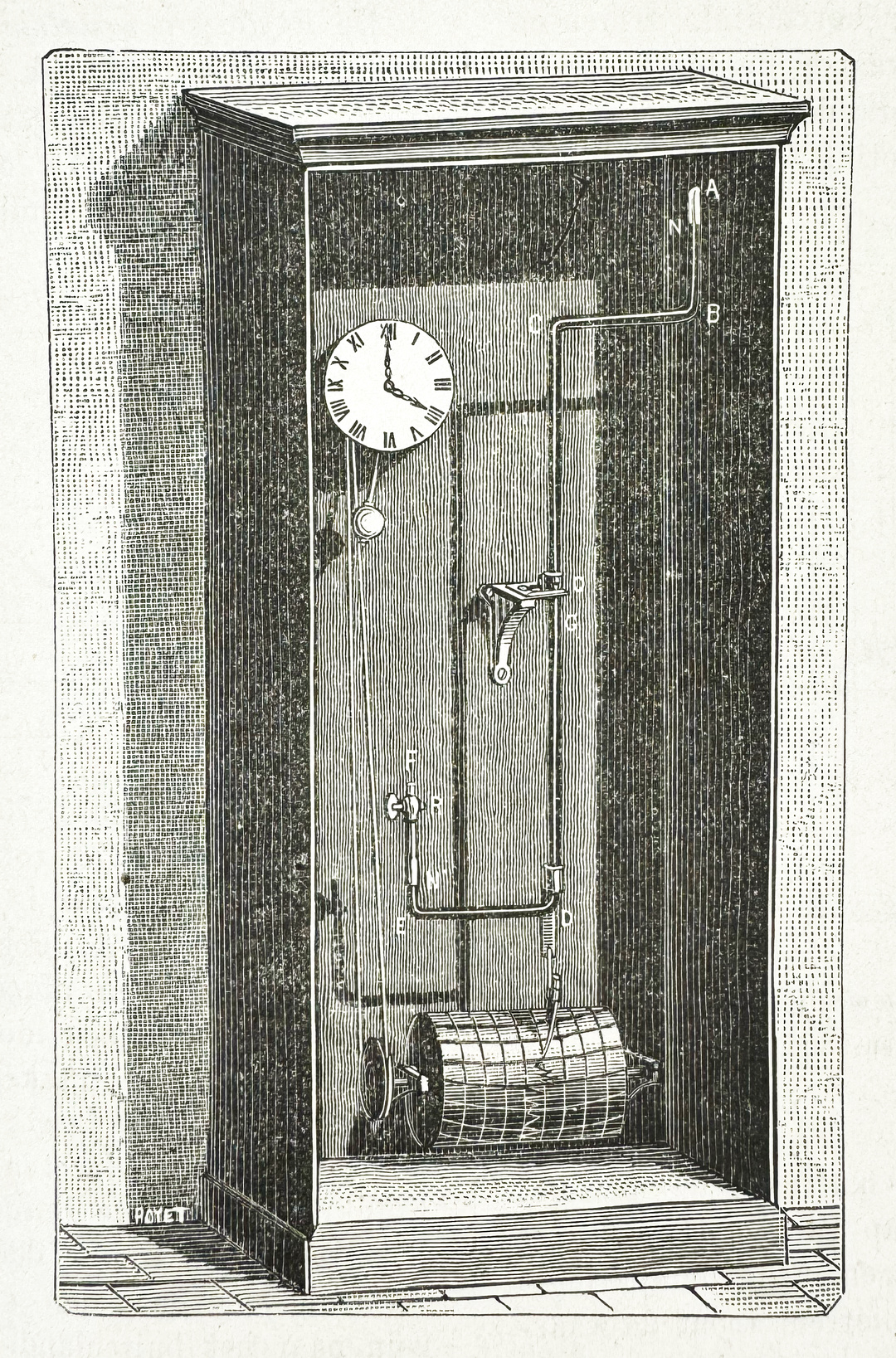

Since the invention of the first barometers, scientists dreamed of creating a device that could automatically record data in real-time. The idea of automating data recording found its first expression in the 17th century. The English scientist Robert Hooke decided that it would be more practical to enhance existing mechanisms. In 1673, he improved and expanded upon the world's first recording meteorological device, created in 1663 by Christopher Wren, the prominent English mathematician and architect. This instrument consisted of a pendulum clock with a cylinder on which paper was rolled, a hammer that struck dots on the paper every quarter of an hour, and several instruments for measuring temperature (at the time, the device did not yet register atmospheric pressure).

This idea laid the groundwork for the creation of mercury self-registering barometers, which combined the achievements of two outstanding instruments — Hooke's wheel barometer and the clock mechanism. In these barometers, changes in the mercury column in the siphon tube were transferred from a float resting on the mercury to a lever that carried the recording mechanism. The lever moved, recording pressure changes on paper on an enlarged scale, while a pendulum clock turned a metal drum on which the paper was wound, gradually unrolling as data was recorded.

Photobarograph

In 1847, Sir Francis Ronalds developed the photobarograph, which used daguerreotype plates to photographically record changes in atmospheric pressure. This device became a significant step in the automation of meteorological observations and was installed at the Kew Observatory.

Over time, self-registering mercury barometers allowed continuous recording of barometric fluctuations not only on paper moving across a drum but also through photographic processes on sensitive plates.

In 1847, Sir Francis Ronalds, a British scientist and inventor, developed and constructed a photobarograph for the photographic recording of changes in the height of the mercury column on a daguerreotype plate. This instrument was later installed and used at the Kew Observatory. In Ronalds' photobarograph, light from an Argand lamp passed through a condensing lens and fell on a narrow slit cut into a metal plate attached to the barometer tube, where mercury, rising or falling, changed the length of the illuminated slit. A lens system projected an enlarged image of the illuminated slit onto an aperture in the case, past which the daguerreotype plate slowly moved clockwise with the help of a clock mechanism, thus recording changes in the barometer's height.

The photographic barometer became a culmination of the scientific achievements of its time, combining elements of mechanics, optics, and early photography techniques.

Barographs

Barographs, invented in the 19th century, used aneroid capsules and clock mechanisms to precisely record pressure changes.

In 1867, at the Paris International Exhibition, the renowned watchmaking company Breguet presented the first aneroid barograph, which immediately attracted attention for its innovative approach to measuring atmospheric pressure. This device was a combination of a precision clock mechanism and highly sensitive aneroid capsules. The instrument used an external flat spring with several interconnected aneroid capsules, which ensured more precise and sensitive measurements. The famous Breguet clock mechanism, known for its accuracy and reliability, played a crucial role.

The barograph was a unique fusion of the precision of a clock mechanism with the responsiveness of barometric capsules, providing reliable data for continuous monitoring of atmospheric pressure. Inside the barograph drum was a spring-driven clock mechanism, which rotated the drum continuously, allowing a paper tape to move evenly. Depending on the complexity of the clock mechanism, the drum could have a running time of anywhere from one day to a month. More commonly, barographs with three- and eight-day runs were found. A time scale with the days of the week was printed on the paper tape, allowing for accurate tracking of pressure changes throughout the recording cycle.

The recording of changes was carried out using a writing lever (hand) connected to the capsule system. As the pressure changed, the capsules compressed or expanded, moving the lever, which left marks on the paper. Early barographs used ink pens as the writing instrument, with a small drop of ink placed in the slit or wings of the pen, depending on the design.

In the 20th century, small attachments with fine markers replaced the ink pens, maintaining their writing function for over a year. Additionally, the clock mechanism inside the drum was replaced by a battery-powered unit.

Observing Nature as a Way of Predicting the Weather

Long before the invention of barometers, people observed natural phenomena to predict the weather. Sailors, whose lives depended on weather conditions, used signs like the behavior of seagulls or sharks to anticipate storms and weather changes. Clouds, sunsets, and other natural phenomena also helped people predict the weather.

Long before the first barometers began showing drops in mercury levels, people already sought clues about upcoming weather by closely observing nature. For sailors, whose lives were deeply connected with the unpredictable ocean, these observations were a matter of life and death. They knew that winds blowing from the sea brought rain, while winds from the land brought dry weather. Foam on the wave crests, glistening in the rays of the setting sun, could signal an impending storm, while calm seas were harbingers of clear, peaceful weather. By watching the behavior of animals and changes in vegetation, fishermen and captains developed entire systems of signs that allowed them to predict storms, strong winds, or long-awaited calm. One such sign was observing seagulls, which, before an approaching storm, would begin to behave restlessly, descending closer to the surface of the water, as if warning the sailors of impending danger. Even more impressive abilities were demonstrated by sharks — thanks to their unique mechanoreceptors, which are sensitive to changes in pressure, sharks can anticipate bad weather and leave dangerous areas long before it strikes.

In addition to observing animals, people carefully watched the clouds. For example, a crimson sunset always heralded a clear day, while a morning red sky warned of an approaching storm. High cirrus clouds drifting overhead indicated the approach of a warm front, while large cumulus clouds could signal the possibility of thunderstorms. Different cultures worldwide developed unique methods for predicting the weather. In China, for instance, farmers used a “snake calendar”: by observing when snakes began to emerge from their burrows, they could determine when the rainy season would begin. In Europe, people linked the position of constellations with harvest forecasts, observing the position of the Pleiades to understand the best time to start sowing. A halo around the Moon or Sun, a ring of thin clouds, was considered a sign of rain, while dim starlight indicated high humidity. Bright stars, on the other hand, warned of approaching frosts. These ancient signs, carefully preserved and passed down through generations, helped people survive and thrive despite nature's whims.

Primitive Tools for Predicting the Weather

People created simple yet effective devices for forecasting the weather. One such device was a pinecone used as a hygrometer. Sheep's wool and hemp ropes also served as humidity indicators, allowing sailors and shepherds to forecast weather changes and prepare for rain.

In addition to observing nature, people have long created simple but remarkably effective tools for predicting the weather, which became reliable assistants in everyday life. These primitive devices, made from available materials, demonstrate the ingenuity and keen observation skills of our ancestors. For instance, one such primitive yet reliable meteorological tool was an ordinary pinecone. It was hung on porches or by windows, and it served as a kind of hygrometer: before rain, the scales of the cone would close tightly under the influence of increased humidity, signaling impending rainfall. In dry weather, when humidity decreased, the scales would open again, as if announcing the continuation of sunny days.

Shepherding communities developed their own method of weather prediction based on the condition of sheep's wool. Wool absorbs moisture from the air and becomes heavy and damp. This method was also actively used by sailors, who scattered sheep's wool across the deck to collect fresh water in the morning, condensed on the fibers during nighttime cooling. For more precise humidity readings, sailors placed wool on a scale: an increase in its weight indicated the approach of wet weather. On ships, hemp fibers used to make ropes also acted as weather indicators. These fibers, due to their ability to swell in high humidity, became a kind of weather predictor: if knots tied in dry weather became tighter and more difficult to untie, it signaled an increase in air moisture and the likelihood of rain.