William Cary was a renowned British maker of scientific instruments in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Born to George and Mary Cary in Corsley, Wiltshire, he was the youngest of four brothers. His elder siblings followed related trades: George became a haberdasher, John became a celebrated map engraver and publisher, and Francis was a copperplate engraver. William, however, pursued a technical path from an early age and apprenticed under the legendary London instrument-maker Jesse Ramsden. Gaining invaluable experience from Ramsden, Cary began his independent career as an optician and maker of “philosophical instruments” (as scientific devices were then called) in the 1780s.

By the end of that decade, Cary had opened his own workshop on the Strand — a hub for scientific instrument makers at the time. His early addresses included 177 Strand (mentioned until 1789) and 272 Strand (c. 1789). By 1794, William had established himself at 182 Strand, from where he gained widespread recognition. He rapidly earned a reputation as one of England’s finest makers of astronomical and mathematical instruments: his products were renowned not only across Britain but also internationally. Cary’s workshop offered an exceptionally broad range of instruments — microscopes, refracting and reflecting telescopes, sextants, compasses, theodolites, pantographs, orreries, and more. Meteorological instruments, such as barometers, held a special place in his production and contributed significantly to his fame.

Many scientists of the era valued Cary’s instruments: the notable chemist William Hyde Wollaston regularly commissioned equipment from him. In the early 19th century, Cary also assisted Wollaston in promoting the use of malleable platinum — a new material for scientific applications.

In 1791, Cary constructed a two-foot transit circle for amateur astronomer Rev. Francis Wollaston — the first such instrument made in England — fitted with optical micrometers for scale reading. The quality of his work was so high that Wollaston presented a report on Cary’s instrument to the Royal Society in 1793. In later years, Cary produced more large astronomical devices: for example, a ~41 cm meridian circle was made for Swiss astronomer Johann Kaspar Fehr around 1790 and is still held at the Zurich observatory. In 1805, Cary sent a large transit instrument to Moscow — and during the Napoleonic campaign of 1812, Napoleon even issued a safe-conduct pass to protect it during military movements.

The prominent astronomer Friedrich Bessel began his early observations in Königsberg using a 2.5-foot altazimuth circle constructed by Cary. His finely crafted sextants and telescopes were also widely used in navigation and geodesy.

Cary was not only a craftsman but also actively engaged with the scientific community. He was a founding (charter) member of the Royal Astronomical Society, established in 1820. In addition to instrument-making, he published regular weather reports in The Gentleman’s Magazine, keeping a meteorological diary for several years — a sign of his commitment to integrating scientific observation into public knowledge.

By the 1820s, William Cary’s name had become synonymous with precision and quality. However, in 1820, the family business suffered a devastating blow: a fire in a neighboring cobbler’s house spread to 181 and 182 Strand, completely destroying both William’s optical workshop and his brother John’s mapmaking office. In half an hour, the blaze consumed all possessions, including a unique collection of model instruments that Cary had built over 35 years.

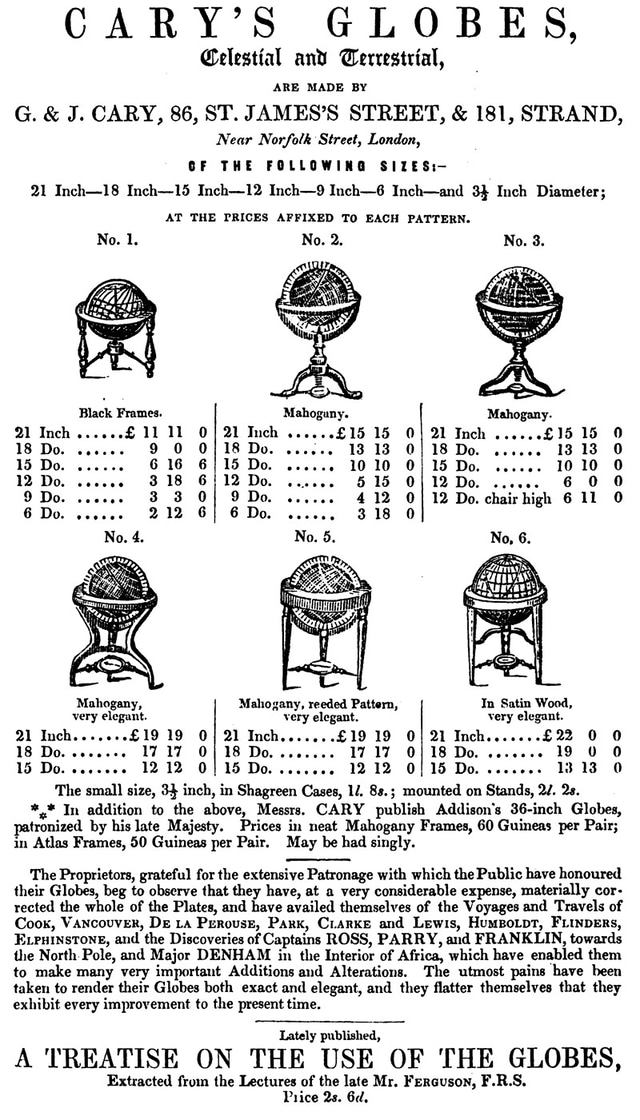

After the fire, the brothers temporarily relocated both businesses to a new address at 86 St James’s Street. Undeterred, William soon resumed his operations: by 1823, he had re-established his workshop on the Strand, now at 277 Strand, and continued working until his death. Cary remained professionally active until the very end and “conducted business with vigor up to his death” at age 66. He died on November 16, 1825, leaving behind a stellar professional legacy and a well-established firm — ready to be inherited by the next generation of the Cary family.

William Cary had no sons, so the business was passed on to the sons of his elder brother, the cartographer John Cary — his nephews George Cary and John Cary Jr. Both were raised and educated in their father’s field of cartography but were also familiar with their uncle’s instrument-making enterprise from an early age. Around 1821, while William was still alive, the two began assisting in managing the family business. Upon William’s death in 1825, they officially inherited the optical firm: his will granted most of his estate to these nephews.

By that time, John Cary Sr. had largely stepped back from daily operations, and his sons took the reins. They made a deliberate decision to retain the established brand — continuing the company under the name “William Cary” in tribute to their uncle’s reputation and legacy.

In the first years after the transition, the business operated from their father’s former premises at 182 Strand (rebuilt after the fire). By 1828, George and John had relocated the instrument-making workshop to the neighboring 181 Strand, thereby reoccupying the same adjoining properties on the Strand that once housed both the optical and cartographic branches of the family business. This close proximity allowed for efficient coordination between the two departments — one focused on scientific instruments, the other on maps and globes.

Although both George and John were trained as engravers and map publishers, they did not possess the same level of mechanical expertise as their uncle William. To maintain the quality of their instruments, they relied heavily on Charles Gould, William’s longtime foreman and craftsman. Gould had worked with William for many years and, after his death, took over much of the technical direction of the firm.

In 1826, Gould designed the now-famous Cary-Gould microscope — a portable field microscope for amateur naturalists, commissioned by the new generation of Carys. Although Gould was the designer, the early models from the 1820s were engraved with “Cary, London”, continuing to leverage the trusted family brand.

During this transitional period, the firm was briefly listed under “J. Cary” (referring to John Sr., their father). But after John Sr.’s death in 1835, George and John Jr. officially reinstated the company name as “William Cary”. This brand identity endured throughout the 19th century, and starting around 1843, the firm’s documents and instrument labels began referring to it as “William Cary & Co.”, reflecting the fact that it was now a company rather than a sole proprietorship.

George and John Jr. continued running the family business into the mid-century. However, over time, their interests leaned increasingly toward the cartographic division inherited from their father. After John Jr.’s death, which occurred shortly after the Great Exhibition of 1851–52, George made the decision to exit the instrument-making trade altogether.

In the early 1850s, he transferred that part of the business to the Gould family, long-time partners in the workshop. Although the enterprise changed hands, the “William Cary” name continued to be used on instruments until about 1856, when Charles Gould passed away and the business was inherited by his descendants.

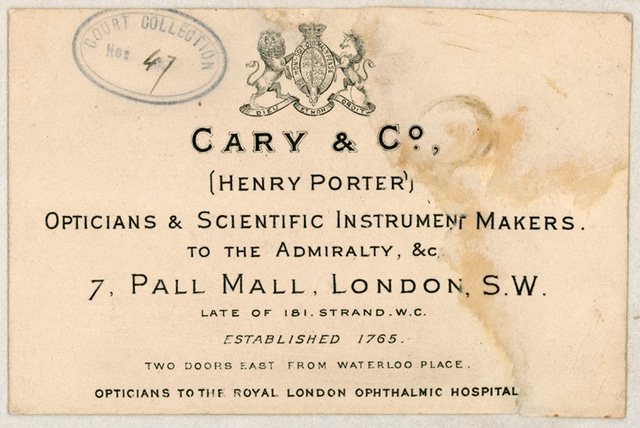

Later, the firm underwent further changes of ownership. By the late 19th century, it was known as Cary, Porter & Co., and it continued trading until the 1930s. Even so, instruments bearing the original founder’s name — “William Cary” — remained in circulation throughout the 19th century, a testament to the enduring legacy and branding established by William and maintained by his nephews and successors.

Alongside their achievements in scientific instrumentation, the Cary family gained prominence in the field of cartography. William’s elder brother, John Cary (c. 1754–1835), was among the leading British mapmakers of his time — an accomplished engraver and publisher of maps and atlases. He launched his independent business in 1782 on Fleet Street and soon relocated to the Strand. John’s reputation grew rapidly through the publication of detailed road atlases and topographical maps of the British Isles, such as his renowned Itinerary and national atlases.

Around 1791, the two brothers — John with his engraving expertise, and William with his technical prowess — entered into an informal partnership to produce globes. This collaboration combined cartographic accuracy with high-quality craftsmanship and quickly established the Carys as major figures in the British globe market.

The Cary globes of the late Georgian era are now considered some of the finest of their time. They featured carefully printed and hand-colored gores (the curved map segments used to cover a spherical surface), applied to sturdy globes mounted on elegant stands. The brothers produced globes of various sizes, ranging from small “pocket globes” (3–6 inches in diameter, often stored in leather cases for travel) to larger terrestrial and celestial globes measuring 12 to 18 inches — intended for educational or library use.

Their collaborative globes typically bore the inscription “J. & W. Cary, Strand, London”, and later versions appeared under “Cary, Strand, London” with publication dates included. These globes were praised for their cartographic precision, aesthetic quality, and accessibility. Today, they are prized items in museum and private collections alike. For instance, an exquisite 3.5-inch pocket terrestrial globe from 1794 by John and William Cary is preserved in the Vienna Globe Museum, displayed on its original stand with an hour circle.

After 1820, particularly following John Cary Sr.’s death in 1835, the cartographic branch of the family business passed to his sons George and John Jr., who had inherited the firm’s engraving presses and copper printing plates. They continued publishing updated maps and atlases during the Regency and early Victorian periods.

However, by the mid-19th century, the Cary brothers began to shift away from active map publishing. Eventually, their engraving plates for both maps and globes were sold to London publisher James Wyld and later to G. F. Cruchley, who reissued the works under the Cary imprint into the late 1800s.

Thus, while the Cary family’s direct involvement in cartography ceased by the 1850s, their influence endured through successive publishers who preserved and republished their work. John Cary Sr., the patriarch of the cartographic branch, passed away in 1835, having left a lasting legacy in British mapping. His globes, made in collaboration with William, remain emblematic of a high point in English geographical and scientific publishing.

The William Cary firm left behind a rich technical legacy, with many of its instruments preserved in museums and private collections. Among the most widely recognized products were the company’s barometers — both wall-mounted mercury types and, later, aneroid models — known for their precision and refined craftsmanship. Elegant stick barometers signed “Cary, London”, often with silvered brass dials and Regency-era detailing, are now highly valued by collectors and feature prominently in antique instrument catalogues.

Cary’s telescopes and spyglasses were equally respected — ranging from small collapsible traveling telescopes to large stationary refractors for astronomical use. These instruments were noted for their optical clarity and durable construction, and were frequently mentioned in early 19th-century trade catalogues.

The firm was also a prominent supplier of nautical instruments. Its sextants and compasses were widely used by British seafarers, and Cary’s name could often be found among the standard equipment aboard naval and merchant vessels of the era. Even during the early 19th-century Arctic expeditions and long-distance voyages, Cary instruments were valued for their dependability.

Numerous examples survive today: for instance, a 10-inch station theodolite and a portable barometer once belonging to Captain George Cary are held in the Science Museum in London. A meridian circle by Cary remains part of the Zurich observatory’s historical collection. Some instruments even entered museum holdings via government agencies, such as those transferred from the British Meteorological Office.

Perhaps the most iconic of all Cary instruments, however, is the Cary-Gould microscope, designed in the 1820s for use by amateur naturalists. This pocket microscope, named after Charles Gould (the firm’s senior craftsman and successor) and marketed under the Cary brand, was a breakthrough in portability and design. Though Gould was its creator, the microscope bore the engraving “Cary, London”, further reinforcing the brand’s authority.

The instrument was cleverly designed: it could be dismantled and stored within a small case that doubled as a stand when reassembled. It became highly popular among botanists, entomologists, and curious gentlemen of the Victorian period. The firm published a companion manual titled “The Companion to the Microscope”, which was reprinted at least 17 times and accompanied many of these instruments.

Numerous examples of the Cary-Gould microscope survive in museum collections — including a well-documented set recently acquired by National Museums Scotland. These instruments, despite their compact size, exhibit meticulous craftsmanship — from finely polished brass fittings to carefully engraved markings.

Besides microscopes, the Cary firm also produced other optical innovations of the time, such as camera obscuras and magic lanterns (early image projectors). Still, the Cary-Gould microscope remains the firm’s most emblematic invention from the post-William period, combining utility, elegance, and accessibility in a single device.

The Cary family’s activities unfolded during the golden age of British scientific instrumentation. William Cary, having apprenticed under the legendary Jesse Ramsden, inherited a direct line of technical knowledge and precision methods that defined the London tradition. Ramsden’s influence was evident in Cary’s use of dividing engines for engraving precise scales — a hallmark of high-end instrument-making in the late 18th century.

At that time, London was a vibrant center of optical and mechanical craftsmanship. Alongside Ramsden, notable figures included Edward Troughton, the Dollond family, and Peter & William Knight. Amid this competitive environment, William Cary not only held his own — he thrived, developing a workshop whose name became synonymous with reliability across Europe.

A defining trait of this period was the preservation of master brands across generations, often long after the founder’s death. William Cary exemplified this: he carefully trained his nephews George and John, who in turn maintained the business under his name even after his passing in 1825. They relied on Charles Gould, a seasoned foreman, to uphold the quality and innovation expected of the Cary name.

This pattern of multi-generational continuity was common in British instrument-making. Workshops were often passed down to relatives or trusted apprentices, while the original founder’s name continued to appear on the instruments. In Cary’s case, tools and devices signed “Cary, London” were still being produced and sold well into the 1890s, long after the original William’s death — a practice similar to that of the Dollonds, Martins, and others.

The Cary firm’s reputation also benefited from interdisciplinary collaboration. The globe-making enterprise, combining John Cary’s map engraving with William’s mechanical expertise, showcased the advantages of merging cartography with instrument-making — a synergy rare even among contemporaries.

Moreover, William Cary maintained close ties with the scientific community. His instruments were commissioned by leading scientists — including William Hyde Wollaston, Johann Kaspar Fehr, and Friedrich Bessel — and built to meet the latest research needs. Cary was listed among the founding members of the Royal Astronomical Society and remained actively engaged with contemporary discoveries and material science (such as the application of platinum in instrumentation).

Responding to broader societal shifts, the Cary firm adapted to the growing amateur scientific market. In the early 19th century, science became fashionable among the educated classes. Cary’s portable field microscopes, travelling telescopes, and compact globes catered to this new clientele of “gentleman naturalists” and traveling scholars.

Collaboration extended through mentorship: Charles Gould carried forward William’s standards, and later, Gould’s son continued the work. In the 1860s, the firm transitioned to Henry Porter, another former Cary-Gould associate, who rebranded the company as Cary, Porter & Co. Under Porter’s management, the company even received international honors — such as a silver medal at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair — proving that the Cary legacy of craftsmanship and innovation remained intact.

In sum, the Cary family’s contribution to British instrument-making was profound. They bridged the worlds of optics, cartography, and mechanics, transmitted skills across generations and collaborators, and responded agilely to both professional and public demands. The “Cary, London” name became a trusted symbol of precision, quality, and elegance — one that graced the desks of astronomers, travelers, and scientists across the globe, and endures today in museums and collections as a testament to a remarkable era of invention.