The company Rodenstock was founded in 1877 in Würzburg (Bavaria) by a young entrepreneur, Josef Rodenstock.

“Born into a poor family, Rodenstock began at the age of 14—without any formal training—by selling sewing needles and porcelain buttons in rural areas of the Rhineland. Later, he began distributing barometers of his own manufacture, as well as self-designed instruments, including a metallic tachometer for breweries and the first eyeglass frames.” — Johannes Buder, “Rodenstock,” in: Neue Deutsche Biographie, vol. 21: Pütter – Rohlfs, edited by Otto zu Stolberg-Wernigerode, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 2003, pp. 695–696.

By as early as 1861, the Rodenstock family had established mass production of mercury barometers—glass tubes were commissioned from the Thuringian Forest, while dials bearing the Rodenstock name were printed in Würzburg. This early success in the manufacturing and sale of physical measuring instruments (particularly barometers) laid the foundation for the future company. From 1872, the enterprise officially referred to itself in invoices as: “G. Rodenstock — Fabrik mathematischer & physikalischer Instrumente” (G. Rodenstock — Manufacturer of Mathematical and Physical Instruments).

In the autumn of 1877, Josef, together with his brother Michael, opened the Optische Werkstätte G. Rodenstock (“G. Rodenstock Optical Workshop”) in Würzburg, naming it in honor of their father Georg (the “G” in the name). The same letter appears in the company’s early logo—a design of two crossed lines ending in circles (possibly stylized tools). The other initials on the emblem are R for Rodenstock and M, likely for Manufaktur or Mathematischer. The logo is crowned with an eight-pointed star, a traditional symbol of enlightened craftsmanship and scientific precision.

Initially, the workshop produced and sold a wide range of products: mathematical, physical, and optical instruments, particularly eyeglasses and pince-nez, as well as small technical devices such as thermometers, scales, and tachometers. Among the company’s offerings were aneroid barometers, opera glasses, and other instruments designed by Josef Rodenstock himself. Barometers, along with eyeglasses, became one of the company’s early specialties. In an 1899 advertisement, “opera glasses and barometers of our own system” were listed among Rodenstock’s core products.

Josef continued to expand the business. He experimented with the production of lenses and frames and showed keen interest in optics. By the late 1870s, he developed his first innovation: diaphragm lenses—eyeglass lenses with a blackened rim to reduce glare. The product became an immediate bestseller and was patented by Rodenstock. Within just two years of founding the company, by 1879, the firm employed about 30 people, and Josef himself earned a reputation as a talented mechanic. The academic staff of the University of Würzburg trusted him with the construction and repair of scientific instruments for physics and chemistry experiments. For his achievements, he was even granted the title of University Mechanic.

Aiming to reach a broader market, Rodenstock relocated operations to Munich—the region’s center of science and technology. From 1882 onward, the firm operated under the name: G. Rodenstock, Fabrikant von physikalischen, optischen und mathematischen Instrumenten (“Josef Rodenstock, Manufacturer of Physical, Optical, and Mathematical Instruments”). The product range expanded substantially, and in 1884, a new retail branch was opened at Karls-Tor, Munich, under the name: Optische Anstalt G. Rodenstock (“Optical Institute G. Rodenstock”), which began offering custom-fitted spectacles to Munich clientele.

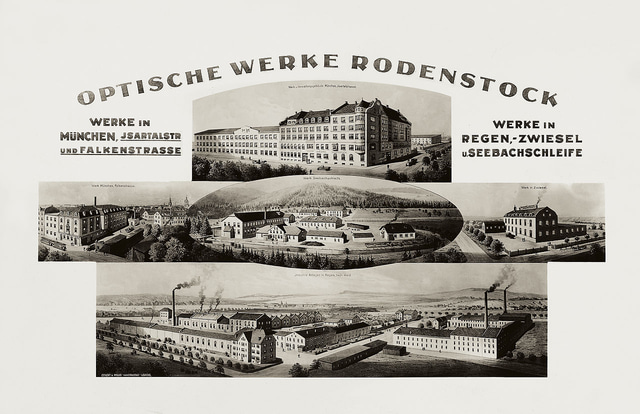

The expansion was rapid: by the mid-1880s, Rodenstock had 17 sales offices and agencies across Germany, Switzerland, Luxembourg, Bohemia, and beyond. Demand kept growing, and the company had to scale up production. In 1886, Josef acquired a property on the outskirts of Munich along the River Isar, formerly a plaster factory. On this site (Isartalstraße), new workshops were established, powered by hydroelectric energy from the river. This address—Isartalstraße 43—would remain the company’s headquarters for decades (until 2012). Meanwhile, Michael Rodenstock moved production from Würzburg to Munich, while Josef focused on promoting the brand abroad. He wrote advertising articles and traveled throughout Europe, establishing partnerships with distributors and offering a wide range of products—from optometers and refractometers to barometer dials and photographic lenses.

During this period, Rodenstock launched its now-famous photographic lens, the Bistigmat, which surpassed competitors in aperture quality and was more affordable. Over 25,000 units were sold within three years. Thus, alongside eyeglass optics, the firm developed a strong second pillar: photo optics. By the end of the 19th century, Rodenstock also produced binoculars, telescopes, opera glasses, and precision measuring devices.

To meet rising demand, Rodenstock envisioned a full-scale industrial lens manufacturing facility. Because expanding within Munich was too costly, he chose the small town of Regen in the Bavarian Forest—a historic center of glassmaking—conveniently located on the Munich–Prague railway line. The new factory opened in 1899, but initially faced difficulties: skilled glassblowers were scarce, and untrained peasants and woodworkers had to be hired, slowing productivity. It was only after Michael Rodenstock took over the plant that production stabilized. By 1905, the Regen facility employed around 250 workers, and a second building was erected to expand capacity. Thus, by the turn of the century, Rodenstock had evolved from a craftsman’s workshop into an industrial-scale manufacturer with factories in Munich and Regen, a national sales network, and growing international reputation.

“Rodenstock was a true master at concealing the origins of his goods. It is confirmed that thermometers came from Greiner (Neuhaus am Rennsteig) and F. Mollenkopf (Stuttgart), based on purchase receipts. As for the barometer mechanisms, no direct documentation exists. It is possible they were supplied by Gebr. Koch, an optical wholesaler in Stuttgart—one of Rodenstock’s most reliable partners at the time. The strongest candidate remains C. Lufft, which began manufacturing barometers in Stuttgart in the same year (1877). Also mentioned are Otto Bohne (1863) and Gischard-Saul (1874). In any case, it is known that barometer dials bearing the Rodenstock name were produced in-house, and the instruments were assembled within the company. … In 1890, Rodenstock began in-house production of aneroid barometers—reportedly up to 5,000 units per year. Barometers became the company’s second most important revenue source, and new custom dials were created for them.” — Gerhard Stöhr, Aneroid-Barometer, die robuste Alternative. Von der Idee zur Realität.

By the beginning of the 20th century, Josef Rodenstock still ran the thriving family business himself, though age and exhaustion began to take a toll. In 1905, he called on his eldest son, Alexander Rodenstock (1883–1953), who left his physics studies at the Technical University of Munich to join the company. At just 22 years old, Alexander began assisting his uncle Michael in production. A young engineer with fresh ideas, he quickly earned trust and introduced a strong research focus to the company, understanding that constant innovation in optics was key to competitiveness. In 1912, Josef redistributed company shares: Alexander and two of his brothers-in-law became co-owners. Full leadership passed to Alexander after 1919, when the 73-year-old Josef retired.

By then, the Rodenstock family had been awarded the title of Court Opticians to His Majesty, serving the German Emperor and King of Prussia, Wilhelm II.

Alexander Rodenstock took over the company during an exceptionally turbulent era. Shortly after he assumed leadership, World War I (1914–1918) broke out, and Rodenstock’s export trade nearly came to a halt. During the war, the company shifted to military production, manufacturing optical equipment—especially precision binoculars and sights—for the German army.

After the war, Germany plunged into economic crisis: hyperinflation, mass unemployment, and a brief recovery in the mid-1920s were followed by the Great Depression in 1929. Despite these extreme conditions, Alexander managed to keep the company afloat. In the 1930s, he successfully resisted an attempted takeover by optical giant Carl Zeiss, and in 1932, when Rodenstock was on the brink of collapse, he secured a major government contract from the Reichswehr (German army), which saved the firm from bankruptcy.

With the rise of the Nazi regime in 1933, the economy was once again mobilized for military needs, and by the late 1930s, the company was once again producing defense-related optical equipment. During World War II, Rodenstock manufactured prisms and scopes for tanks, “Robra” gas mask goggles for the military, and continued large-scale production of eyeglass lenses, which were considered strategically important goods and thus exempt from restrictions.

In 1944, the Munich factory was heavily damaged during air raids, though not completely destroyed. Just three weeks after the war ended, the American occupation authorities granted permission for Rodenstock to resume operations. Production was partially transferred to the undamaged plant in Regen, which began supplying the Allies with camera lenses, binoculars, and optical components.

Despite the company’s loyalty to the regime during the war, Alexander Rodenstock himself was targeted by the Nazis because his wife was of Jewish descent. After Germany’s defeat in 1945, during the denazification process, Alexander was temporarily removed from leadership due to his designation as a “Wehrwirtschaftsführer” (leader of the war economy), a title that raised suspicion. An external administrator was appointed to lead Rodenstock for two years.

However, in 1947, a tribunal of the Allied Control Council fully cleared Alexander, determining that he had no compromising ties to the Nazi regime. He returned to his position and began rebuilding the business.

Still, years of stress had taken a toll on his health. (In 1919, during the early days of the Weimar Republic, he had even been taken hostage by revolutionary sailors who threatened to execute him.) In 1953, Alexander Rodenstock passed away at the age of 70, handing over the company to the next generation.

Leadership then passed to his son, Rolf Rodenstock (1917–1997). Rolf had joined the business during the final year of the war (1944) and held a doctorate in economics. His tenure coincided with the “economic miracle” of postwar West Germany and the subsequent decades of growth. Under his leadership, Rodenstock became the dominant player in the West German optics industry, focusing on research and international expansion.

By the late 1950s, the company achieved a major breakthrough with the introduction of mass-produced bifocal lenses. In 1968, Rodenstock launched the first photochromic (self-tinting) lenses in Europe. The company also expanded into related fields: from 1960, it began manufacturing eyeglass frames in-house, and it released a range of precision optical devices, such as Splendar projection lenses for slide projectors.

During the 1970s, Rodenstock expanded internationally, opening subsidiaries in Austria and France (1965), Italy (1972), and the United States (1975). As early as 1951, Rolf had co-founded Industria Optica Rodenstock in Santiago, Chile—this South American factory would later become part of the Rodenstock Group and a leading lens supplier in the Chilean market.

Rodenstock consistently proved itself a pioneer: in 1975, during the oil crisis, it became the first company in the world to produce plastic eyeglass lenses, which significantly reduced frame weight. In 1980, the company launched Progressiv R, its own brand of progressive lenses, offering smooth transitions between focal zones and replacing traditional trifocals.

The 1980s marked the company’s transformation into a global corporation. By the end of the decade, Rodenstock had 7,000 employees worldwide, and annual revenues approached 700 million Deutsche Marks. To strengthen its global competitiveness, part of the traditional manufacturing was relocated abroad: in 1989, Rodenstock built a large lens production plant in Thailand, while frame manufacturing was concentrated in Malta.

Meanwhile, a new generation of the Rodenstock family was preparing to take the helm. In 1990, Randolf Rodenstock (b. 1948), great-grandson of the founder, succeeded his father Rolf as managing director, continuing the family tradition in its fourth generation. Like his predecessors, Randolf had a background in physics and economics and initially combined corporate work with academic teaching. But his leadership began during a difficult era: the 1990s brought increased global competition, market deregulation, and healthcare reforms in Germany, all of which sharply reduced domestic demand for eyeglasses.

In 1989, Rodenstock posted its first financial loss, with sales dropping by nearly 20%. Facing the threat of bankruptcy, Randolf implemented aggressive restructuring: a large portion of production was shifted to Asia, where lenses and components were manufactured at modern factories in Thailand, benefiting from lower costs. The main factory in Regen was converted into a research and logistics center, and the company invested heavily in new lens technologies: e.g. Multigressiv, Cosmolit Office with progressive designs, advanced coatings, and improved photochromic performance.

Rodenstock also worked on refreshing its brand image: by the mid-1990s, major ad campaigns were launched, and partnerships with brands like Porsche Design and Reebok helped create fashionable eyewear collections. These efforts paid off: by 1994, the company returned to profitability. By the end of the decade, Rodenstock held a 50% market share in Germany, was #2 in Europe, and #3 worldwide in eyeglass optics. Yet new challenges lay ahead.

In the early 2000s, Rodenstock faced a severe crisis in the U.S. market, prompting a major corporate restructuring. In 2002, the company was reorganized as Rodenstock GmbH, with its lens and frame production spun off into the new entity. After more than 125 years of family ownership, the Rodenstock family sold a majority stake in 2003 to the private equity firm Permira. This marked the end of the Rodenstock family’s control over the company, although Randolf remained a consultant for several years.

In 2006, Permira sold the company to Bridgepoint Capital, which in turn transferred ownership in 2016 to Compass Partners, and in 2021, the Rodenstock Group was acquired by Apax Partners. Despite the changes in ownership, the Rodenstock brand remains one of the world’s leading manufacturers of optical systems.

The company entered the 21st century true to its legacy of innovation. In 2018, Rodenstock introduced DNEye Pro, a technology for measuring biometric eye parameters to customize lenses. In 2020, it launched the B.I.G. Vision™ (Biometric Intelligent Glasses) concept, setting a new benchmark in personalized optics. Today, Rodenstock specializes in lenses, frames, and sunglasses, collaborates with brands like Porsche Design, and is active in more than 85 countries around the world.

It is possible to find Rodenstock catalogues and price lists in which the company name is followed by the phrase “Nachf. Optiker Wolff GmbH” — meaning “successor Optiker Wolff GmbH.”

This does not refer to the Rodenstock manufacturing enterprise itself, founded by Josef Rodenstock, but rather to its retail and diagnostic division, known as the “Optisch-oculistische Anstalt Jos. Rodenstock.” This was a network of optical institutes and salons where eyesight examinations were carried out, spectacles were fitted, and both in-house products and items made by the Rodenstock factory were sold.

Such institutes existed in various German cities — primarily in Munich and Berlin. They functioned as independent branches: each had its own address, staff, equipment, and accounting, but operated under the authoritative Rodenstock name. Over time, some of these branches came under the management of business partners or were purchased by other companies.

This was the case in the late 1920s and early 1930s, when the optical company Optiker Wolff GmbH took over several Munich and Berlin Rodenstock locations, including the institutes at Bayerstraße 3, Marienplatz 17, and Joachimsthaler Straße 44. The new owners acquired not only the premises and customer base but also the right to display in their signage and printed matter the formula of succession — “Optisch-oculistische Anstalt Jos. Rodenstock, Nachf. Optiker Wolff GmbH.”

Thus, the Rodenstock name remained on these documents as a recognizable mark of high quality, while legally and organizationally these establishments were already operated by the Wolff company. The Rodenstock family firm itself continued to exist independently, developing the production of lenses and frames that remained in the hands of the founder’s descendants well into the twenty-first century.