R. Deutschbein was a Hamburg-based mechanician of the mid-19th century, specialising in the manufacture of aneroid barometers and related instruments. In contemporary sources he is referred to explicitly as a “barometer maker”. His period of active work falls primarily in the 1870s. The Science Museum in London records that R. Deutschbein was active in Hamburg around 1874–1875, although other evidence suggests that this timeframe may be extended somewhat beyond those years.

At the International Exhibition of Scientific Apparatus held in London at the South Kensington Museum in 1876, R. Deutschbein presented a substantial series of his instruments. In the official report by Rudolf Biedermann (1877), his exhibits are listed as follows: a standard aneroid barometer, an aneroid with visible movement, two “metal barometers” of his own design, and two “spring barometers of the Reitz system” (German: Feder-Barometer, System Reitz)—all shown with their internal mechanisms exposed. The first four instruments were described as “domestic barometers distinguished by good performance, elegant form, and low cost”, a characterisation that attests to the high quality of Deutschbein’s products combined with relatively moderate pricing. The latter two instruments—the Reitz-system spring barometers—were intended for meteorological observations and for altitude measurement, such as in the surveying of roads, railways, and tunnels. This indicates the maker’s ambition to move beyond purely domestic instruments and toward precise measuring devices for engineers and surveyors.

The address of R. Deutschbein’s workshop in Hamburg is given in city directories as ABC-Straße 36. A newspaper notice from the 1870s mentions “R. Deutschbein, mechanician, ABC-Strasse 36”. In the same context appears advertising by the firm Greiner, a dealer in optical and physical instruments, suggesting that ABC-Straße was a recognised centre for the trade in scientific instruments. It is therefore highly likely that Deutschbein’s workshop was indeed located at this address.

The core of R. Deutschbein’s production consisted of Vidie-type aneroid barometers—that is, liquid-free barometers based on the deformation of a sealed metal cell (the aneroid capsule) under changing atmospheric pressure. It is probable that Deutschbein actively supplied his movements to other German and Danish manufacturers, who incorporated them into their own barometers. Further development of Deutschbein’s ideas led to the creation of so-called Circular barometers, which were visually striking at first glance and distinguished by a number of structural features. One surviving example—a circular aneroid barometer in a mahogany case with the movement openly visible—is dated to 1876 and preserved in the collection of the Science Museum. This instrument is explicitly signed “R. Deutschbein, Hamburg”.

Deutschbein offered models in which the internal mechanism was deliberately exposed behind the dial (mit sichtbarem Werk). This approach not only impressed the public but also allowed direct observation of the behaviour of the aneroid capsule and levers as pressure changed.

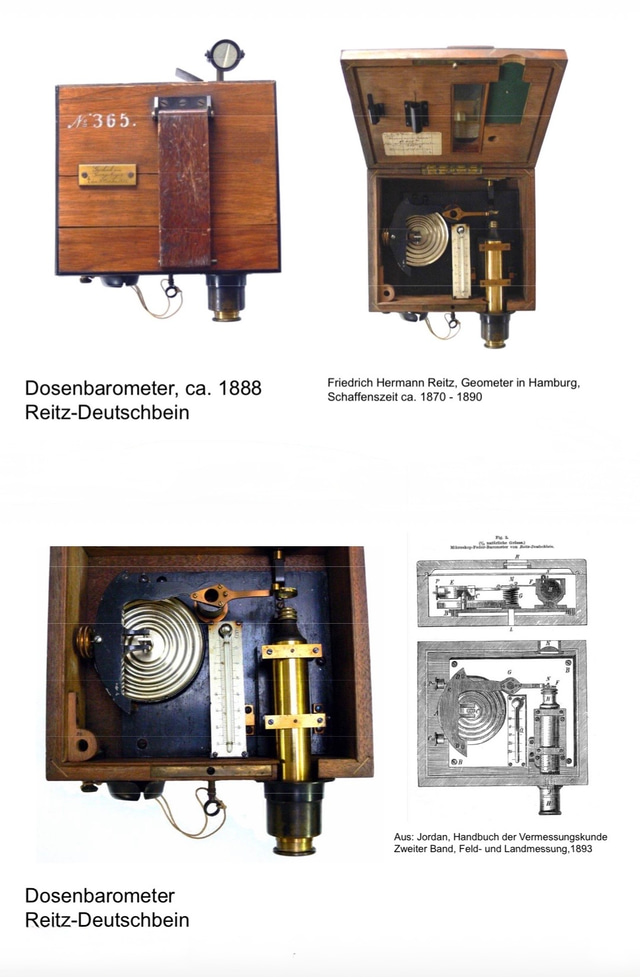

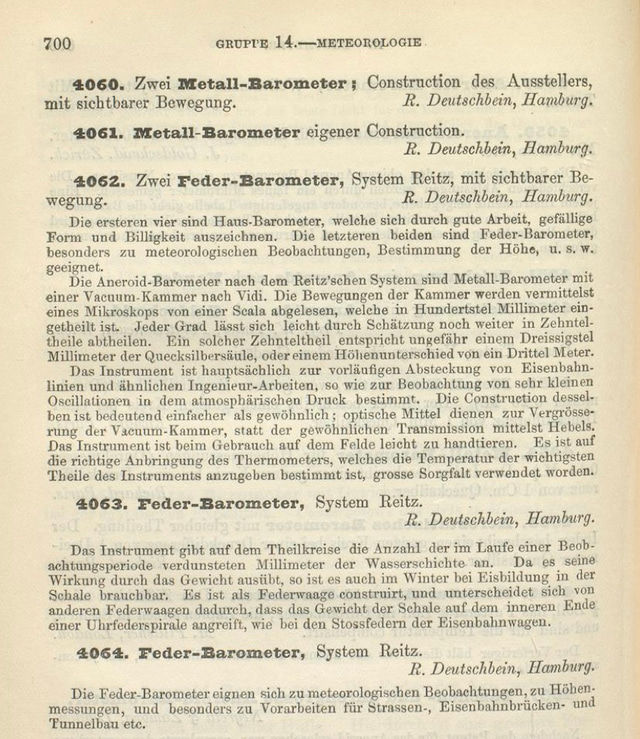

Another important line of development was the creation of high-precision optical aneroid barometers. These instruments are associated with what was known as the “Reitz system”, after F. H. Reitz, a Hamburg-based engineer and surveyor. In 1874, Friedrich Hermann Reitz devised an aneroid barometer of fundamentally new design, the manufacture of which was carried out in R. Deutschbein’s workshop. The defining feature of the Reitz–Deutschbein barometer was the abandonment of the conventional pointer and geared transmission. Instead, the instrument employed an optical readout system: a lever attached to the aneroid capsule was counterbalanced by a spring, and the lever’s displacement was observed through a small measuring microscope.

Behind the microscope was a miniature scale produced by microphotography and applied to a small glass plate. This scale, only 3 mm in length, was divided into 100 parts, each corresponding to 0.01 mm. When viewed through the microscope’s eyepiece, the observer aligned the crosshair with a mark on the lever, allowing pressure changes to be read with a resolution down to thousandths of a millimetre of mercury. The instrument thus functioned in effect as a portable precision barometer-altimeter. Converted into practical terms, 0.01 mm on the scale corresponded to approximately 1⁄30 mm of mercury, or roughly 0.33 m of altitude change. The design was intended specifically for geodetic use—for railway route reconnaissance, levelling, and the detection of subtle atmospheric pressure variations.

Contemporary assessments of the optical barometer were generally favourable. In the technical press of the time it was referred to as the Federbarometer nach Reitz’schem System (“spring barometer of the Reitz system”). It was emphasised that in this instrument “instead of the usual lever transmissions, the movement of the aneroid capsule is read by means of a strongly magnifying microscope”. Reports of the German Alpine Club from 1879 note that Deutschbein had begun producing the Reitz barometer in a reduced, portable form: “Deutschbein in Hamburg now makes the spring barometer of the Reitz system also in smaller dimensions. This instrument fits into a small wooden case…” Thus, a compact optical altimeter suitable for travellers and mountaineers became available.

In practice, however, the Reitz–Deutschbein instrument proved complex and expensive, and its advantages were not unequivocal. Professor Karl Jordan, who tested the new device, observed that in order to cover the full pressure range from 780 to 500 mm of mercury, the optical scale would need to be extended to a length of 11 mm. According to Jordan, Deutschbein was already producing models with a 5 mm scale, but even this was insufficient. Comparative trials conducted in the 1870s showed that a conventional French Naudet aneroid often matched or exceeded the accuracy of the new system. As reported in Polytechnisches Journal, the Deutschbein instrument (still not fully run-in) performed less well than a standard Naudet barometer that had already been “seasoned” through use. While it was acknowledged that the Reitz system offered advantages for stationary observations of pressure variations, for practical levelling work the compact and robust Vidie/Naudet aneroids remained preferable. Nevertheless, the fact that the new barometer was subjected to detailed analysis in the technical literature and even cited in late-19th-century surveying textbooks as the “Reitz–Deutschbein barometer” attests to its historical significance in the development of scientific instrumentation.

The professional activity of R. Deutschbein appears, on the evidence available, to have been relatively short-lived. After the late 1870s his name no longer appears among manufacturers of scientific instruments. There is no indication that the firm continued under the management of heirs or was sold to a successor; at least, the name Deutschbein does not persist in later catalogues. It is likely that the workshop closed, possibly owing to the death of the maker or his withdrawal from business. The engineer F. H. Reitz, with whom Deutschbein collaborated, continued his career in geodesy but likewise did not establish an independent instrument factory.

Nevertheless, the inventions associated with R. Deutschbein left a lasting mark. The “Reitz–Deutschbein system” is cited in historical surveys of barometer development as one of the earliest examples of an optical barometer. Although it did not achieve widespread adoption, the experience gained from its creation influenced subsequent work on precision pressure-measuring instruments.

R. Deutschbein of Hamburg thus stands as a noteworthy figure in the history of 19th-century instrument making. In a relatively brief span of activity, he developed and presented a range of innovative barometric instruments, from domestic aneroids to complex opto-mechanical systems. His workshop combined the traditions of precision mechanics with a spirit of innovation fostered through collaboration with scientifically trained engineers. Although the firm did not survive its founder, Deutschbein’s instruments—now rare items in museum collections—bear witness to the level of sophistication achieved by German scientific instrument making at a time when meteorology and geodesy were emerging as exact sciences.

Sources