Kollsman Instruments Corporation – an American company founded in 1928, which became one of the leading manufacturers of aviation instruments. The firm gained its greatest fame thanks to the development of the precise barometric altimeter, invented by its founder Paul Kollsman. This “sensitive” barometric altimeter turned out to be a key element for safe instrument flight, allowing pilots to determine altitude even in the absence of visibility.

Paul Kollsman, an engineer and immigrant from Germany, arrived in the USA in 1923 and soon began working at the Pioneer Instrument Company in New York, gaining experience in aircraft instrument production. However, Kollsman had his own inventive ideas. In 1928, he left Pioneer and, together with his brother Otto, founded his own company, Kollsman Instrument Company, in Brooklyn with only $500 in savings. Kollsman’s main goal was to create a fundamentally new altimeter for aircraft. At that time, only simple barometric altimeters existed, with errors reaching several hundred feet, which was acceptable only in clear weather. Paul Kollsman, however, conceived of an instrument suitable for “blind” flying—accurate enough for a pilot to rely on in the absence of external visibility.

Already in 1928, Kollsman designed an innovative high-sensitivity barometric altimeter that reacted to the slightest changes in atmospheric pressure. Tests showed that the new instrument could measure altitude with accuracy within a few feet—two orders of magnitude better than its predecessors. For its time, this was a revolutionary achievement. The first public use of the altimeter took place on September 24, 1929: the legendary pilot James (“Jimmy”) Doolittle made the first fully blind flight in history—a 15-kilometer trip in zero visibility, relying solely on instruments, among which the Kollsman altimeter played the key role. The test was successful. Doolittle noted that Kollsman’s instrument “worked flawlessly,” providing accuracy about an order of magnitude better than previous altimeters (about 10 feet, ~3 m). This triumph convincingly demonstrated the feasibility of instrument flight.

Soon after Doolittle’s successful flight, the invention was recognized by aviation authorities and customers. Kollsman’s company received its first major order—the US Navy purchased 300 altimeters to equip naval aviation aircraft. This marked the young firm’s first commercial success. In the early 1930s, Kollsman Instrument Company launched serial production of altimeters, opening its own facilities in Elmhurst (New York) and Glendale (California).

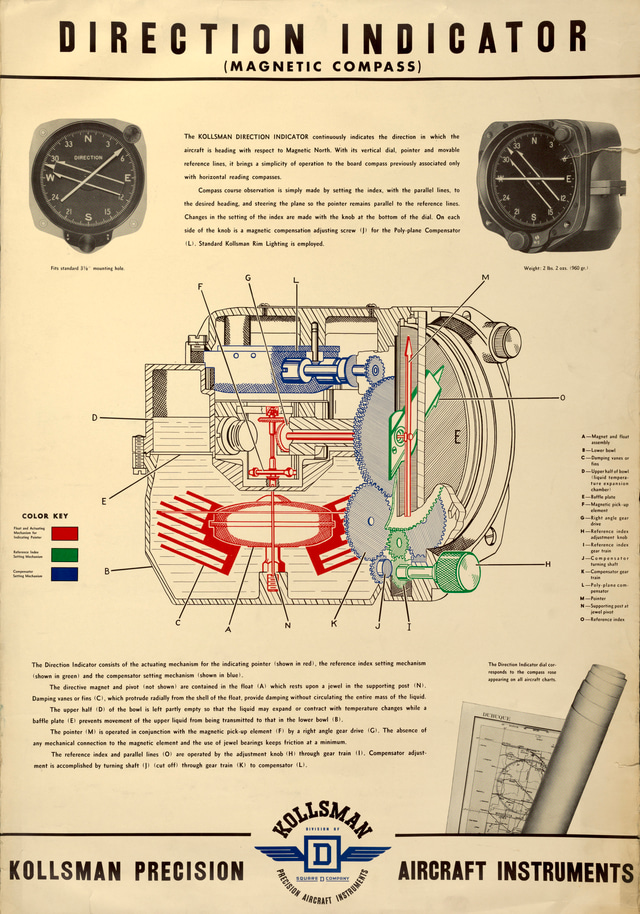

Kollsman’s barometric altimeter was essentially a sensitive aneroid barometer adapted for convenient reading by pilots. Inside the sealed case of the instrument was an elastic aneroid element (a thin-walled corrugated capsule), which compressed as external static air pressure increased (i.e. with decreasing altitude) and expanded as pressure decreased (with increasing altitude). A system of levers and gears converted the microscopic changes in the capsule’s shape into pointer movements on the dial, showing the current flight altitude.

Altimeters of this type were usually equipped with a multilayer dial and several hands, each indicating a different order of magnitude, similar to a clock. For example, one design had three coaxial hands: a long thin hand (with a triangular tip) showing tens of thousands of feet, a short wide hand showing thousands of feet, and a long narrow hand showing hundreds of feet. Thanks to this system, the pilot could read absolute altitude with high precision. The key innovation in Kollsman’s design was the presence of a special barometric scale window on the dial, which allowed adjustment for current atmospheric conditions. By turning an adjustment knob, the pilot set in this “Kollsman Window” the sea-level pressure value received from weather services or the departure/arrival airport. Thus the instrument was calibrated to real conditions, and its zero mark corresponded to the airfield’s elevation. This innovation eliminated errors caused by daily pressure variations and ensured correct indication of absolute altitude above sea level.

The Kollsman altimeter became known in aviation as the “Kollsman Window,” after the pressure-setting window. This principle of altimeter setting later became standard on all barometric altimeters worldwide. Thanks to its high sensitivity (able to detect altitude changes on the order of 1–3 m) and correction for pressure, Kollsman’s instrument provided unprecedented accuracy and opened the era of safe cloud and night flying.

The success of Kollsman’s altimeter in aviation was rapid. By the mid-1930s, these instruments dominated the altimeter market. Almost all new aircraft in the USA were equipped with Kollsman altimeters, displacing competing models. Kollsman altimeters quickly spread internationally as standard equipment on both civilian airliners and Allied military aircraft. The company expanded production: in addition to the New York plant, an assembly facility in California opened, reflecting growing demand.

Besides altimeters, the firm began developing other cockpit instruments. In the 1930s, Kollsman introduced artificial horizons, course indicators, navigation instruments, and others, expanding its presence in the cockpit. Thus Kollsman Instruments gradually became one of the leading suppliers of integrated avionics solutions. For his invention of the precise barometric altimeter and contribution to aviation, Paul Kollsman received wide recognition, including the prestigious Guggenheim Medal for aeronautical achievement. By the end of the decade, the name “Kollsman” had become synonymous with reliable flight instruments vital for safety.

In 1940, on the eve of US entry into World War II, the founders decided to sell the company to a strategic investor. Kollsman Instrument Company was sold to Square D Corporation (Detroit), a well-known producer of electrical equipment, for over $4 million. Paul Kollsman retained a management role, becoming a vice president of Square D and heading his former company as a division of the new owner. This allowed the combination of Square D’s resources and Kollsman’s technical expertise to ramp up instrument production during wartime.

With the onset of World War II, Kollsman altimeters and other aircraft devices became critical components for the US and Allied armed forces. The Square D (Kollsman) division worked at full capacity, supplying thousands of instruments to front-line aviation. For example, sensitive altimeters of the AN-C12 type, developed by Kollsman, were installed on almost all USAAF aircraft during the war. These altimeters measured up to 50,000 feet and featured the pressure-setting window—essentially an evolution of Kollsman’s 1929 design. The company also contributed to other military programs, producing optical and navigation instruments including bombsights and aeronautical sextants for long-range bombers. Kollsman altimeters proved so reliable that they remained in service even after the war, being retrofitted (e.g. replacing radium-lit dials with safe ones) and upgraded at depots up to the 1980s.

The wartime period marked further company growth and innovation. Paul Kollsman was listed as inventor or co-inventor of numerous technical solutions—by 1945 he held over 100 patents, and by his death in 1982, 124 patents. The accumulated engineering experience enabled the company to branch into new fields after the war. In particular, Kollsman became a pioneer in high-precision optical instruments: in the postwar years it developed a series of astro-sextants for aircraft and spacecraft. One such Kollsman sextant was used on the Apollo 13 spacecraft in 1970, helping astronauts navigate their return to Earth.

In the 1950s the company underwent several ownership changes. In 1951 Square D sold the Kollsman division to Standard Coil Products Co. of Chicago, a manufacturer of radio components (notably TV tuners), for over $5 million. After this, Paul Kollsman finally left the company, and long-time employee Victor Carbonara became general manager. Under Standard Coil, the company retained the Kollsman brand and profile while becoming part of a diversified business. Soon the owner’s name was changed to Standard Kollsman Industries Inc., emphasizing the brand’s recognition and continuity.

Within Standard Kollsman, the enterprise continued producing aircraft instruments while also expanding into related fields. In addition to avionics, the company produced electromechanical components for consumer electronics and automobiles. For example, Standard Coil was historically a major supplier to the television industry, and after the merger, Standard Kollsman produced parts and kits for TV tuner repair. At the same time, aircraft instrument development continued, including new barometric altimeters for jet aviation, gyroscopic instruments, and military devices (sights, navigation systems, etc.). By the early 1970s, Kollsman even had overseas assets, such as the subsidiary Kollsman System-Technik GmbH in Germany for the European market.

In 1972, Standard Kollsman Industries itself was acquired by Sun Chemical Corporation (formerly Sun Ink), a major chemical-industrial conglomerate, as part of a diversification strategy. The deal (via stock exchange) was worth about $10.3 million. Sun Chemical had not previously been involved in avionics, but the acquisition of Standard Kollsman marked the start of a new division producing instruments and systems for aviation and automotive industries. The Kollsman units were retained as separate groups within Sun Chemical (aviation instruments and automotive components). Thus the Kollsman brand continued within a large conglomerate. In subsequent years Sun Chemical, under financier Norman Alexander, transformed increasingly from chemicals to high-tech manufacturing. By the mid-1980s, the parent company, renamed Sequa Corporation, had become predominantly an aerospace and defense concern, with Kollsman’s legacy playing a major role.

By the 1980s–1990s, the Kollsman brand functioned as a Sequa division specializing in defense electronics and aviation systems. Building on its instrument expertise, Kollsman expanded into modern electro-optical systems. In the 1980s, for example, the division helped create advanced pilot training simulators. In 1989 Kollsman (as part of Sequa) won a $26.7 million contract to supply Top Gun air combat training systems for USAF and USN centers. The company developed airborne transmitter pods and ground tracking stations enabling pilots to practice dogfighting maneuvers without live fire and later review flights in debriefing halls. This success cemented Kollsman’s reputation as a supplier of high-tech military solutions. During this period the company also produced head-up displays (HUDs), night vision devices for pilots, and laser rangefinders and sights for aviation, expanding well beyond analog instruments.

Seeking greater international presence in aerospace technologies, in the 1990s Sequa looked for strategic partners and investors for its divisions. Eventually, Kollsman’s US business was acquired by Elbit Systems, the Israeli defense firm. Kollsman became part of Elbit Systems of America, where it continues to function. Its headquarters are in Merrimack, New Hampshire.

In the 21st century, Kollsman remains a leader in aircraft systems. Building on more than 90 years of experience, it develops and produces a wide range of modern avionics—from classical altimeters and air data systems to advanced electro-optical systems. According to the company, today Kollsman offers a complete set of solutions: air data systems, flight and navigation instruments, HUDs, thermal imaging, and enhanced vision systems (EVS) for pilots. Kollsman products are installed on military and civilian aircraft worldwide. For more than two decades the company has been a key supplier of Enhanced Vision Systems for Gulfstream business jets, improving flight safety in poor visibility.

Throughout its history, Kollsman Instruments has remained true to its mission—providing pilots with accurate and reliable flight information. From the first barometric altimeters that gave aviation the ability to fly in clouds to today’s integrated avionics, the name Kollsman continues to stand for altitude, innovation, and a commitment to excellence in flight instrumentation. The company, which began as one inventor’s workshop, still shapes aviation, preserving a unique legacy while developing new technologies for future generations of pilots.

Sources: