Julius Nissen was a Danish maker of scientific instruments active in the mid-nineteenth century. He was born on 29 December 1817 in southern Denmark. In 1834, at the age of sixteen, he moved to Copenhagen in order to learn the craft of scientific instrument making. Nissen entered an apprenticeship under the well-known master Henrik Poulsen, who headed the instructional workshops of the recently founded Polytechnic Institute (Polyteknisk Læreanstalt). At the same time, Julius attended evening courses at the Technical Institute, where he demonstrated exceptional ability: he was awarded a prize for fine metal engraving and, upon completing his eight-year apprenticeship, successfully passed examinations in physics, mechanics, and technical drawing.

As early as 1836, while still a student, Nissen presented his first instrument at an industrial exhibition in Copenhagen. In 1840, he exhibited a dividing engine of his own construction, several thermometers, and a model of a high-pressure steam engine; these exhibits were favourably noted in contemporary reports. After completing his training, Julius Nissen undertook an extended educational journey abroad between 1841 and 1843, lasting approximately one and a half years. During this period, spent in foreign workshops, he acquired advanced skills in glassblowing — an essential competence for the manufacture of precise thermometers and barometers. This experience laid the foundation for his later career as an instrument maker and optician.

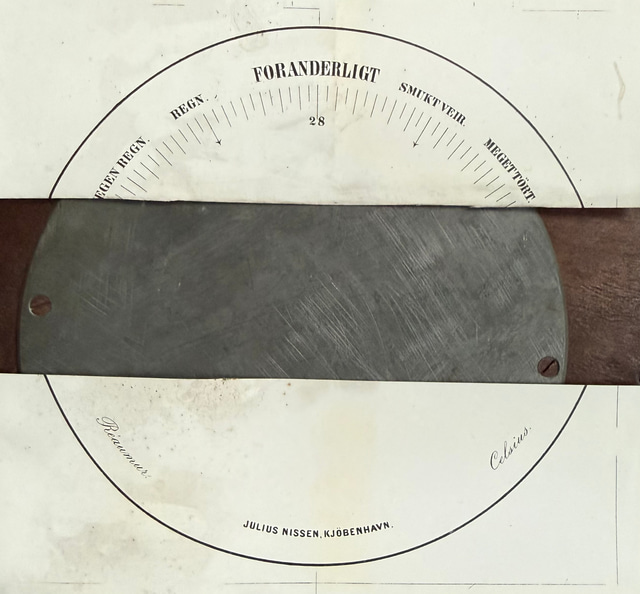

Upon returning to Denmark, Julius Nissen established his own workshop for physical and meteorological instruments in Copenhagen. His business was located on Købmagergade in the city centre and later maintained a branch in Helsinki (then Helsingfors). Nissen described himself as a “meteorological instrument maker and glassblower,” a designation that accurately reflected his professional focus on instruments for measuring atmospheric and physical phenomena. By the mid-1840s, his products had already gained recognition.

In 1844, Nissen improved the standard Spandrup alcoholometer, an instrument used to measure alcohol strength. He integrated a thermometer directly into the alcoholometer and sealed the scale within the glass. This innovation made the instrument easier to use and eliminated the possibility of discreet manipulation of results, since earlier measurements required consultation of a separate thermometer. As a result, alcohol strength measurements became more reliable, and Nissen’s name became closely associated with the further development of the so-called “normal” Spandrup alcoholometer.

Nissen’s workshop expanded rapidly. He actively introduced new developments and was, for example, among the first in Denmark to sell stereoscopes; from 1857 onward, this novel optical device was available through his firm. At the same time, his enterprise produced a wide range of scientific instruments. Contemporary accounts indicate that at its height the workshop employed up to eight journeymen and workers, enabling the production of both precision measuring instruments and apparatus for scientific demonstrations. Alongside his own manufacture, Nissen also traded in advanced foreign-made instruments, consistently aiming to provide Danish scientists and the educated public with the most up-to-date technical equipment.

Instruments and Achievements

The range of instruments produced by Julius Nissen was extensive. He specialised in meteorological instruments, including thermometers, barometers, and hygrometers. Among these were psychrometers — paired thermometers used to determine air humidity — as well as other complex instruments for climatic observation. In addition, his workshop manufactured air pumps (vacuum pumps), precision balances and weight sets for analytical chemistry, precious-metal assay, and laboratory use, along with various forms of laboratory equipment.

Nissen also demonstrated notable inventive talent. In addition to the improved alcoholometer, he designed an efficient single-cylinder, two-stroke air pump of his own construction. This pump combined simplicity with economy of operation and brought him international recognition.

Barometers occupied a particularly important place in Nissen’s work. It is known that he produced high-quality wall barometers, including traditional column-type instruments. These barometers were distinguished by refined design and carefully executed scales. It is highly likely that, following the expiration of Lucien Vidie’s aneroid patent, Nissen was among the first makers in Denmark to manufacture aneroid barometers. Initially, these closely followed Vidie’s original construction with an external coil spring, while later examples appear to incorporate alternative mechanical solutions, including counterweight systems. Nissen movements are encountered in barometers made for the German, Dutch, and French markets, although it remains unclear whether these instruments were produced entirely in Nissen’s own workshop or whether only the movements were exported.

Nissen’s workshop also supplied other meteorological instruments. He produced standard thermometers of various types, whose quality benefited directly from his personal mastery of glassblowing and his ability to draw uniform, fine capillary tubes. Long-term accuracy of scales was ensured by means of a dividing engine that Nissen had constructed early in his career. In this way, Julius Nissen established himself as a versatile and highly skilled maker of precision scientific instruments.

International Recognition and Awards

Julius Nissen achieved recognition not only in Denmark but also internationally. The culmination of his success came with the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, the first World’s Fair held at the Crystal Palace. Nissen was invited to present his work as part of the Danish exhibition and made a strong impression. The exhibition catalogue lists his contributions, which included a two-stroke air pump, sets of laboratory balances (for chemical analysis, precious metals, and assay work), standard weight sets, as well as barometers, a psychrometer, and thermometers of his own manufacture.

The jury particularly praised Nissen’s air pump, for which he received an award at the exhibition. Contemporary accounts report that this pump earned either a medal or an honourable mention as an outstanding combination of originality and affordability. By the mid-nineteenth century, Nissen’s name had thus become known within European scientific circles.

Beyond the Great Exhibition of 1851, Nissen regularly participated in national industrial exhibitions in Denmark. His instruments were displayed repeatedly in Copenhagen during the 1830s and 1840s, and new thermometer models were shown at the Danish industrial exhibition of 1852. His improved alcoholometer was adopted by the Danish customs service for alcohol control, underscoring the practical importance of his work.

Although Nissen did not receive royal orders or decorations, he enjoyed high esteem among scientists and instrument makers. During the 1860s, Professor Adam A. Junger, who was involved in the construction of major astronomical instruments, collaborated with Nissen; in 1867 they even shared the same address in Copenhagen, despite specialising in different fields. Junger focused primarily on astronomical instruments, while Nissen concentrated on physical and meteorological apparatus, making their workshops complementary rather than competitive.

Pupils and Successors

Julius Nissen was not only a prolific maker but also a teacher of the next generation of Danish engineers and instrument makers. His most notable pupil was Christopher Peter Jürgensen (1838–1913), later a professor and industrialist. Jürgensen entered Nissen’s workshop in 1851 at the age of thirteen and trained there for eight years, until 1859. Like his master, he attended evening courses at the Technical Institute and, due to his outstanding performance, received a scholarship for study abroad.

After his return, Jürgensen continued to work under Nissen and Professor Junger. When Junger retired from active business in 1869, Jürgensen took over his mechanical establishment. He carried forward the traditions of Nissen’s workshop and gained renown as a maker of astronomical instruments before later redirecting his enterprise toward bicycle production. Nevertheless, the fundamental skills of precision mechanics that underpinned his success were acquired during his apprenticeship with Julius Nissen.

Within the family, the immediate successor was Christian Nissen (born 1849), Julius’s son. From an early age, Christian assisted his father and specialised in the manufacture of thermometers and barometers, having mastered glassblowing. After Julius Nissen’s sudden death in December 1867, the eighteen-year-old Christian assumed control of the workshop. For a time, the firm continued under the name “Julius Nissens Efterfølger” (“Successor to Julius Nissen”), preserving the established reputation. However, Christian Nissen died at a young age, and the direct family line of production came to an end. Remaining craftsmen transferred to other enterprises, including that of Christopher Jürgensen, allowing the technical knowledge of Nissen’s workshop to persist beyond the family itself.

Significance and Legacy

Julius Nissen lived a relatively short but remarkably productive life devoted to the advancement of scientific instrument making. He died on 8 December 1867 in Copenhagen at the age of fifty. Over the course of his career, he made a substantial contribution to equipping Danish scientific institutions with modern instruments. His name is firmly associated with the flourishing of Danish precision instrument making in the mid-nineteenth century.

Nissen may rightly be regarded as one of the pioneers of industrial meteorological instrument production in Scandinavia. His thermometers, barometers, and alcoholometers were valued for their quality and found use both in Denmark and abroad. His innovations — from improvements to standard measuring instruments to the early commercial introduction of stereoscopes — demonstrate both technical ingenuity and entrepreneurial vision.

Despite lacking a formal academic title, Julius Nissen was recognised as an authority by scientists of his time. His instruments facilitated accurate experiments and meteorological observations, contributing to the progress of the natural sciences. Today, his legacy survives in museum collections and private holdings: examples of his barometers, thermometers, and other instruments can be found in institutions such as the Den Gamle By museum in Aarhus, as well as among important collections of historical scientific instruments. His life and work stand as a clear example of how a single skilled craftsman helped lay the foundations of a national tradition in scientific instrument making.

Sources