Frédéric Japy (1749–1812) was an outstanding industrialist, the founder of the family company Japy. In 1777, in his native village of Beaucourt (Franche-Comté), he opened a small clockmaking workshop. Having received a traditional watchmaker’s training in Switzerland under the master Abraham-Louis Perrelet, Japy returned with a cutting-edge idea – to mechanise the manufacture of clocks. In the 18th century every spring and gear wheel was still cut by hand, but Japy invented and introduced machine tools for series production of clock movements (the so-called ébauches – movement blanks). For the first time in France he created a factory for watch movements (1777), laying the foundations of modern industrial production. Thanks to mechanisation, by 1795 about 400 workers were already employed in his plant – an incredible number for those years.

Japy’s entrepreneurial success was accompanied by social innovation. A convinced Protestant, he treated his workers in a paternal way. Frédéric created factory settlements for his employees – the “Japy colonies” (cités Japy), where the workers lived, ate and were provided with everything they needed on the factory site. The factory buildings housed canteens, kitchens, dormitories and sleeping rooms. Japy himself said: “I want my workers to form one family with me. My workers must be my children and at the same time my collaborators.” This paternalistic model, ahead of its time, ensured cohesion of the workforce and improved the living conditions of the labourers. Later the Japy heirs continued this tradition, building workers’ housing estates, schools, hospitals and mutual-aid funds in the region.

Frédéric Japy patented a number of his own inventions. For example, in 1799 he obtained a patent for ten horological machines – among them a gear-cutting machine, a screw-thread cutting machine and a lathe for machining watch plates. He stressed that his mechanisms were so simple that even children or people with disabilities could operate them. Japy also made early use of the power of nature: in 1793, when he bought an old watermill in Badevel at a sale of nationalised property, he foresaw the use of water power to drive factory machinery.

Frédéric came from a prosperous Protestant family. His father Jacques Japy was mayor of Beaucourt and a blacksmith; Frédéric himself received a good education. In 1806, at the age of 57, he decided to retire from business and handed over management of the company to his elder sons. A few years later, having outlived his wife, Frédéric Japy died in 1812, leaving sixteen children and a flourishing enterprise. In honour of the founder, the Frédéric-Japy Museum was opened in Beaucourt, exhibiting his inventions and the firm’s products.

The Japy dynasty: family succession and growth of the company

After Frédéric Japy’s withdrawal in 1806 the firm took the name “Japy Frères” (Japy Brothers), after the three brothers who inherited the business. The eldest son, Fritz-Guillaume (Frédéric Guillaume, known as “Fritz”), took charge of commercial and financial management; the second, Louis-Frédéric, was responsible for technical development and the design of new machines; the youngest, Pierre, oversaw production and quality control. This family structure allowed the business to prosper over several generations. The third generation of the Japys continued the success, although the initial technological lead gradually diminished.

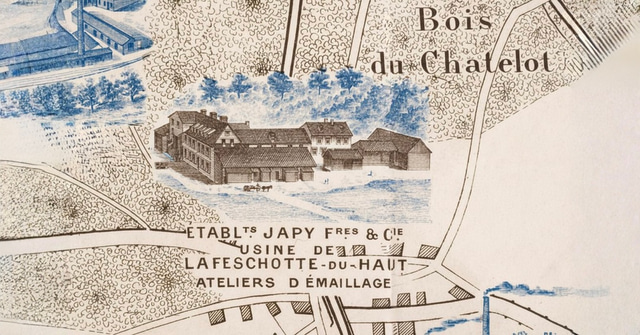

The Japy brothers immediately expanded their activities beyond clocks. In 1806 they also founded a small metal-goods works (quincaillerie) on the site of the old mill. By 1810 Japy Frères had developed a machine for drawing steel wire, and by 1828 a machine for producing nails and screw threads. The family established new factories: in 1826 enamelling workshops were opened in Fesches-le-Châtel, and in 1830 Japy produced its first stamped metal cooking pot of its own manufacture. The diversity of products grew rapidly.

The golden age of the company fell in the mid to late 19th century. By the 1860s–1880s Japy Frères had become one of the largest industrial groups in France. As early as 1863 its share capital reached 5.375 million francs – by this measure the firm was the second largest in France during the Second Empire (after the Schneider metal-works). The Japy empire embraced up to nine factories in the Montbéliard region, employing about 5,000 workers. The family’s wealth was so great that it built 13 private mansions (châteaux) in the environs of Beaucourt. Production capacity continued to expand: new plants were opened – for example at Laroche (Voujeaucourt, 1860), Martine (Hérimoncourt, 1863), Gros-Pré (Dampierre-les-Bois, 1889) and others.

Innovation and production in the 19th century

Technological innovation was the key to Japy’s success. Frédéric Japy is regarded as one of the founders of modern industry in France – he is ranked alongside Armand Peugeot as a pioneer of industrialisation in the Montbéliard region. The company Japy introduced a mechanical production line for clocks: all stages of assembly – from the manufacture of gears and plates to the finished movement – were concentrated in the factory instead of being distributed to home workers. This made it possible to increase volumes sharply and reduce the cost price of clock products. In the first half of the 19th century Japy products (movement ébauches) became widespread among watchmakers throughout the country, effectively standardising the industry.

Beyond clocks the Japys became pioneers in numerous related fields. By the mid-19th century, under the Japy Frères brand, the following were produced: *Clocks and movements: pocket and mantel clocks, wall pendules, alarm clocks, as well as separate clock movements sold to other firms. *Mechanics and metal goods: all kinds of hardware (quincaillerie) – locks, hasps, hinges, screws and bolts. Thanks to their own steel-making skills, the Japys even produced steel wire, springs and tools for watchmakers. *Engines: in the second half of the 19th and early 20th century the company moved into engines (oil, gas and electric), generators, rheostats and small electric motors. Under the Japy brand pumps were also produced (hand pumps, agricultural equipment). *Household goods: from the 1820s–1830s the firm made metal kitchen utensils (cast-iron and enamelled cookware). It was Japy that in 1830 produced the first stamped tin cooking pot in France, and subsequently set up mass production of enamelled pots, kettles, basins and so on. Japy coffee mills also became widely known – robust wooden and metal hand-grinders that could be found in practically every French home. *Furniture and interior items: a more unexpected line was furniture – the company made, for example, garden benches and bent-wood chairs, as well as gas and kerosene lamps, lanterns and other lighting devices. *Bicycles and automobiles: Japy supplied parts for bicycles (spokes, hubs, etc.). At the beginning of the 20th century, when the automobile industry was emerging, the Japy factories had the potential to participate in that sector as well.

A particularly illustrious chapter was the manufacture of Japy typewriters. In 1907 the firm purchased a patent from the Americans Remington and released its first typewriter. This line quickly grew: under the Japy name new models appeared, from heavy office machines to portable ones, in various formats and even colours. In the 1950s–60s Japy typewriters were a symbol of the modern office: designers constantly improved typing speed and key comfort, introducing innovations (for example, the Japy P951 model allowed four-colour typing and had several spacing settings). The brand’s typewriters contributed to women’s emancipation by opening the profession of typist and secretary to them. Despite its success, in the post-war years this division faced difficulties – eventually “Japy dactylo” was sold to the Swiss firm Hermès (the last Japy models were even assembled at the Robotron plant in the GDR until 1981).

Exhibitions, awards and contribution to industrialisation

The achievements of Japy were regularly recognised at the major industrial exhibitions of the 19th century. Already at the early French national industrial exhibitions (Expositions des produits de l’industrie française) the Japy family won numerous medals: gold medals in 1819, 1823, 1827, 1834 and 1839, then silver medals in 1844 and 1849. These awards showed that Japy movements were considered the best in the country.

At the Paris Universal Exhibition of 1855 Japy Frères received the highest award – the Grand Medal of Honour (Grande médaille d’honneur). This triumph allowed the company to place the inscription “Médaille d’Honneur, Exposition Universelle 1855” on its movements as a mark of quality. Twelve years later, at the 1867 Universal Exhibition in Paris, Japy repeated its success and again received the Grand Prize (the highest award). At the 1878 exhibition the firm exhibited hors concours, with the status of a renowned multiple prize-winner. In addition, Japy Frères received honorary diplomas at regional fairs – for example, the Grand Diplomas of industrial exhibitions at Besançon (1879) and the Swiss Le Locle (1880).

Such awards not only promoted the brand but also reflected Japy’s contribution to the industrialisation of France. Frédéric Japy is rightly regarded as one of the “fathers of the French industrial revolution”: he was the first to mechanise watchmaking, preparing the ground for the later industrial leap. Moreover, in the Montbéliard region his activity stimulated the emergence of other enterprises. It is known that, inspired by Japy’s success, in 1810 near Montbéliard the Peugeot brothers (Jean-Frédéric and Jean-Pierre Peugeot) founded their own firm Peugeot-Frères, at first supplying watchmakers with steel springs and later moving on to tools, saws and then the production of coffee mills and bicycles. Thus the Japy dynasty gave impetus to the development of an entire industrial cluster in eastern France.

At the World Exhibitions of the second half of the 19th century Japy clocks and movements competed with the best examples worldwide. A number of Japy mantel clock models were commended by juries for the quality of the movement and the richness of their cases. The medals obtained by the firm were reflected in its product markings: from the 1850s onwards movements bore the stamp “Japy Frères, Médaille d’Or”, later “Grande Médaille d’Honneur”. Recognition at exhibitions strengthened Japy’s reputation as an exemplary manufacturer and secured orders throughout Europe.

The trademark: scrollwork and stars

Japy Frères products are easily recognisable by their distinctive trademark. In the mid-19th century an elegantly engraved logo appeared on movement plates and product plaques – a stylised monogram “Japy Frères & Cie” in the form of the letters J and F set crosswise, with the letter C superimposed at their centre; decorative scrolls are accompanied by four small stars. This mark became a kind of guarantee of authenticity and quality for Japy pieces.

Historically, Japy’s branding evolved. In the early years items might be stamped with Frédéric’s own name (some movements are signed “Louis Japy fils” or simply “Japy”). After 1854 the official name became “Japy Frères & Cie”, and this is what was applied to the products. In 1850–1858 a mark including the phrase “Médaille d’Or” (after the gold medal received) was used. After 1888 a renewed stamp was introduced: “Japy Frères & Cie, Médaille d’Honneur” – already with a small cross shown in the centre of the emblem. Perhaps this cross referred to the Legion of Honour or another distinction. Alongside the main logo, various specialised trademarks also appeared on different types of Japy products. For example, on some early-20th-century coffee mills the firm used the image of a cockerel and stars (a symbol of hardened steel). Nevertheless, the classic logo with the monogram and three stars remained the best-known sign of the Japy house, embodying its rich history.

Range of products: clocks with barometers, coffee mills, typewriters and more

The variety of Japy Frères output ranged from miniature clock movements to heavy equipment. Clockmaking remained the core of the business: the firm produced clocks of every kind – from tiny alarm clocks to impressive longcase clocks. Moreover, Japy not only sold finished clocks under its own name, but also supplied thousands of standard movements to other clockmakers (in France such a movement was known as a “mouvement de Paris”) for casing. Thanks to this, clocks with a Japy “heart” were distributed across Europe.

A special place was occupied by mantel and shelf clocks combined with barometers. In the Victorian era elegant instruments came into fashion – paired ensembles of clock, barometer (and sometimes thermometer) made in the same style. Japy produced such garnitures: for example, there are well-known wall clocks with barometers in carved wooden cases, and bronze clock-barometers for the mantel. It should be noted, however, that like many clockmakers, Japy did not usually manufacture the barometric mechanisms themselves. They assembled their clocks using ready-made aneroid barometers from specialised makers.

The decline of the empire and the fate of the legacy

The rapid rise of Japy Frères was followed by a gradual decline in the 20th century. There were several reasons. First, the loss of family control: in 1921 the Japy family, needing fresh capital, issued bonds and part of the shares passed into outside hands. Management of the company no longer entirely belonged to Frédéric’s descendants, which led to disagreements. Second, the economic depression of the 1930s dealt a heavy blow: the Great Depression reduced sales, factories ran at half capacity and unemployment rose. In 1933 the oldest works at Badevel was closed, and clock production was concentrated only at Beaucourt. Despite reorganisation, the company never regained its former strength.

In 1955 the final break-up of the Japy empire took place. Internal conflicts between the family and the new co-owners led to the division of the concern into four independent companies. The unity of the brand disappeared. Various branches and workshops passed to new owners. In particular, the famous clock division was sold to Jaz of Wintzenheim (Haut-Rhin), and thus the “Japy” name vanished from new alarm clocks, replaced by the Jaz brand. The typewriter division, as already mentioned, went to Hermès. The production of kitchenware and enamelware passed through several changes of ownership and was eventually revived on the same site under the new brand Cristel: the Cristel mark was registered in 1983, and in 1986 the former Japy factories at Beaucourt were bought by the Dodane family, who set up a successful manufacture of high-end stainless-steel cookware there. As for the legendary Japy pumps, this line too did not disappear: the enterprise “Pompes Japy” was later transformed into a cooperative and continues to produce industrial pumps, bearing the founders’ name.

By the late 1970s only fragments remained of what had once been a huge corporation. In 1979 the last of the companies bearing the Japy name was liquidated. It was then that the mechanographic (office-machine) factory at Beaucourt finally closed – 202 years after Frédéric Japy founded his business. Yet the dynasty’s heritage did not vanish into oblivion. In Beaucourt, on the initiative of former employees and local authorities, a Japy museum was opened as early as 1986. It is housed in a historic factory building dating from 1892 and, after restoration in 2012, has become a true monument of industrial history. The exhibits include all kinds of products – from old alarm clocks and typewriters to enamel advertising signs, coffee makers, motors and pumps. Each display case tells of a particular stage in the Japy saga, showing how a small family workshop turned into a giant, and then disappeared, leaving a rich legacy.

The Japy Frères dynasty has entered history forever as a symbol of French industrialisation. From Frédéric Japy’s innovative clocks and machine tools to mass-produced household goods accessible to every family, this name embodied technical progress for almost two centuries. The scrolls of the trademark with three stars can still be found on surviving mechanisms and vintage objects, reminding us of the brilliant and dramatic story of the Japy firm.

Sources: