This article is based on data from the outstanding website www.goldschmid-aneroide.com, where the most detailed information on this subject can be found.

The story of this company begins with the craftsman Johann Georg Oeri. Having studied mechanics under the famous Jean Nicolas Fortin in Paris, Oeri returned to Zurich and in 1808 founded a mechanical workshop at Trittlistrasse 34. Oeri quickly became renowned for his precision instruments – his finely crafted screws and measuring devices were praised by the Hamburg mechanic Johann Georg Repsold and Zurich physicist I.K. Horner. His workshop specialized in mathematical, physical, and optical instruments, including barometers, and laid the foundation for a dynasty of instrument makers.

In 1832, Oeri took on as an apprentice a young mechanic from Winterthur – Jakob Goldschmid. Jakob proved to be a talented pupil and after completing his training, embarked on the traditional journey to other workshops (1835–1838). Upon his return, he married Oeri’s daughter Johanna, becoming both son-in-law and business partner. After Oeri’s death in 1852, Jakob Goldschmid fully took over the workshop and continued its work.

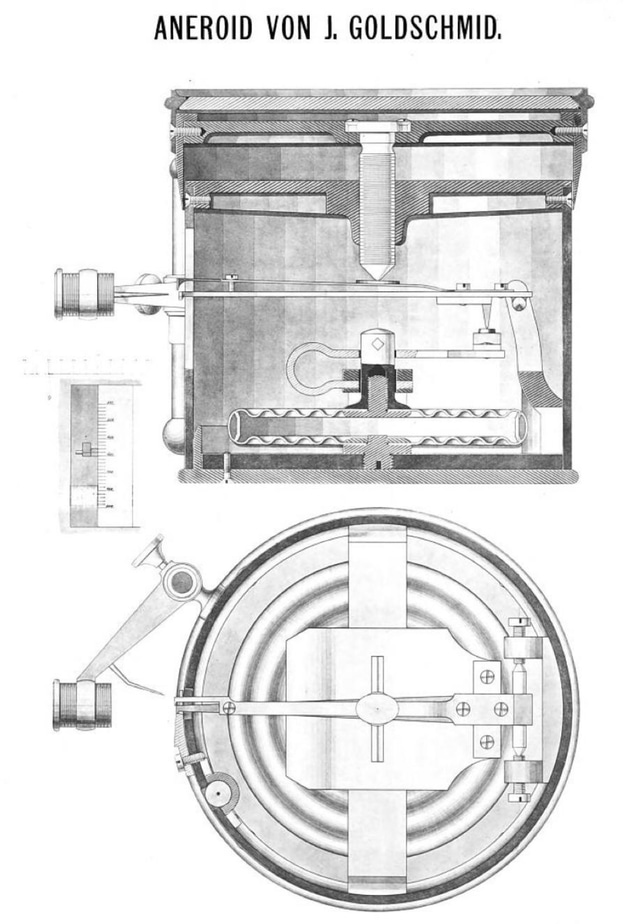

Jakob Goldschmid (1815–1876) is the central figure of this story, thanks to whom a whole line of aneroid barometers of the Goldschmid system was born. In the mid-1850s he developed a portable, mercury-free barometer with an elastic vacuum chamber (aneroid). The innovation stood out for its entirely mechanical principle of operation and high reliability: it could be transported easily, unlike bulky mercury barometers, while still providing sufficiently accurate readings. Goldschmid sought to make his device suitable for precise altitude measurements, and according to contemporary reports, he succeeded – the new “travel barometer” immediately earned recognition among experts.

In subsequent years Jakob Goldschmid created a number of original instruments. In 1861, for example, he invented the “diastimeter” – an optical rangefinder for military use, whose special eyepiece directly displayed the distance (in paces) to the target. Goldschmid also designed the first Swiss recording barometer (barograph) with aneroid capsules. In 1873, at the Vienna World Exhibition, he presented his barograph, for which he was awarded the Progress Medal. In this instrument, a drum with attached paper was driven by a clockwork mechanism, while a lever-and-pen assembly recorded pressure fluctuations on the paper strip. In this way, Goldschmid became one of the pioneers of automatic registration of atmospheric pressure.

Equally important, Goldschmid shared his expertise generously and trained a new generation of craftsmen. Under his leadership, the next generation of specialists was formed, which continued to perfect the “Goldschmid barometer” after the inventor’s death in 1876.

His son-in-law and immediate successor was Rudolf Hottinger (1834–1883), an engineer by training. Even during Goldschmid’s lifetime, in 1871, Hottinger had entered into the business. After Jakob Goldschmid’s death, he continued to run the workshop together with Dr. Carl Koppe, who had been invited as a partner. For about a year and a half, the firm continued under the name “Jakob Goldschmid, Mechanische Werkstätte in Zürich,” until in 1878 it was renamed “Hottinger & Cie, successors of J. Goldschmid”. Carl Koppe, an enthusiastic supporter of Goldschmid’s aneroids, was co-owner of the enterprise until 1881, when he received a professorship and withdrew from the business. Hottinger remained sole head of the firm and managed it until his death in 1883 .

With his engineering talent, Rudolf Hottinger undertook further improvements of Goldschmid’s instruments. He modernized the construction of the barograph: in particular, he changed the orientation of the rotating drums, increased the number of aneroid capsules, and added a special spiral spring for improved accuracy and recording stability. These modifications significantly enhanced the reliability and practicality of the instruments. Under Hottinger’s leadership, aneroid barometers of the Goldschmid system gained wide circulation not only in Switzerland but across Europe. Contemporary observers noted that in this improved form, the “Goldschmid barometer” rapidly displaced other types of aneroids, and sometimes even mercury barometers, becoming indispensable for precision altitude surveys and scientific research. A striking example was the large-scale barometric survey of a railway line (~400 km) in Germany in 1880–1883: it proved that portable Goldschmid aneroids (in Hottinger’s version) could, with sufficient accuracy, replace traditional geodetic methods. For his instruments, Hottinger’s firm won recognition at exhibitions, including awards at the Swiss Industrial Exhibition in Zurich. Thus, Rudolf Hottinger succeeded in developing Goldschmid’s legacy, consolidating the reputation of the Zurich workshop as a manufacturer of first-class precision instruments.

Professor Carl Koppe (1844–1910) was not formally the owner of the company, but he played an outstanding role in the history of the Goldschmid barometer. As a young geodesist, he became interested in Swiss aneroids, and after Goldschmid’s death he joined Hottinger to jointly manage the workshop. Koppe can be called the chief popularizer and theoretician of the Goldschmid system – he extensively researched the properties of aneroid barometers and published many works on the subject. In his articles and books (for example, “Die Aneroid-Barometer von Jakob Goldschmid und das barometrische Höhenmessen”) he deeply analyzed the operation of aneroids, methods of barometric leveling, and advocated recognition of these instruments’ merits among scientists.

Although some colleagues considered him overly theoretical, his contribution is hard to overestimate. He tirelessly promoted Goldschmid’s barometers, emphasizing their high accuracy and convenience, thereby fostering demand. Koppe also consulted Hottinger on technical matters and assisted in implementing improvements in the instruments’ construction. For example, his mathematical calculations and recommendations contributed to optimizing the elastic components and scales of aneroids for more precise altitude measurement. Leaving the Zurich workshop in 1881 for a professorial chair, Carl Koppe remained an authority in scientific instrumentation and made a significant scientific contribution to the refinement of aneroid barometers.

Professor August Weilenmann (1843–1906), a Swiss physicist and meteorologist, carefully studied Goldschmid’s aneroids and published a series of works dedicated to their construction and use. Weilenmann did not limit himself to theory – as a practical man, he proposed his own version of an improved aneroid. This modified instrument, known as the “Weilenmann aneroid,” was indeed built (in small numbers) and named after him. In Weilenmann’s design, ideas for increasing accuracy were implemented: for example, a more massive and sensitive mechanism with a larger number of sizable vacuum chambers. However, these improvements made the instrument bulky and heavy, so the “Weilenmann barometer” did not achieve wide circulation. Nevertheless, the attempt at modernization demonstrated the potential for further development of the Goldschmid system.

August Weilenmann was a respected professor of physics in Zurich and actively introduced the latest meteorological instruments into practice. He directed a network of weather stations, engaged in theoretical meteorology, and was well aware of the needs of scientific observation. His proposals for enhancing the aneroid reflected a desire to increase the sensitivity and stability of the instrument for precise scientific measurements. In this way, Weilenmann’s work complemented Koppe’s contribution, ensuring the all-round development of the Goldschmid barometer – both in theory and in practice.

After Hottinger’s death in 1883, leadership of the renowned Zurich workshop passed to engineer Theophil Usteri-Reinacher (1841–1918). Usteri was the grandson of Johann Georg Oeri himself (his mother Emilie Oeri was the founder’s daughter), making Goldschmid a distant relative. As a student, Theophil was already familiar with the workshop: in his matriculation form of 1859, he listed his address as “at the mechanic Goldschmid”. Having graduated as a mechanical engineer, Usteri worked in machine-building enterprises (including Escher Wyss) and spent some time abroad gaining experience.

On his return, Theophil Usteri-Reinacher took over the Goldschmid (later Hottinger) firm and succeeded in bringing it to unprecedented scale. Under his direction, the workforce expanded to 25 employees – a record in the history of the enterprise. Usteri significantly broadened the product range: besides aneroid barometers, production now included various precision instruments. The firm manufactured geodetic equipment (levels, theodolites), meteorological instruments (thermographs, hygrographs, self-registering rain gauges), and even specialized machinery for industry – devices for testing materials, control instruments for cement and textile factories, power plants, etc. Naturally, Goldschmid system barometers continued to be produced and refined, but they became only part of a wide catalog. A substantial share of the company’s work now consisted of calibration, repair, and adjustment of instruments – service had become an important sector of the business.

During Usteri-Reinacher’s leadership, the company gained international recognition. At the 1889 Paris World Exhibition, his collection of self-registering meteorological instruments was awarded a gold medal. The report noted that under Usteri, the firm had become one of the world’s largest producers of recording meteorological instruments. Theophil Usteri personally designed several successful innovations – for example, an improved continuous barograph (with an external spiral compensation spring), new telescopes, and even a military rangefinder intended to replace stereoscopic periscopes. For his contributions to Swiss precision mechanics, Usteri rose in the army to the rank of captain of engineers, emphasizing the link between his technical activity and national defense.

By the 1900s, the aging Usteri was looking for a partner or successor. In 1909 he placed an advertisement seeking a business partner willing to invest. No one came forward, and only in 1916, two years before his death, was a suitable candidate found – the young engineer Hans Mettler.

Hans Mettler (1882–1965) became the last owner of the celebrated Zurich workshop. On April 1, 1916, he formally took over the business from Theophil Usteri-Reinacher, as announced in the newspapers. Mettler, a graduate in mechanical engineering, continued the firm under his own name, preserving its traditional profile and address (Zurich, Trittlistrasse 36). For a long time this chapter was forgotten, and collectors of barometers mistakenly assumed that the Goldschmid story had ended with his sons. Only later did it become known that engineer Mettler successfully produced Goldschmid’s instruments for more than a decade.

According to the Schweizerische Militärzeitung of 1933, Hans Mettler was described as “the owner of the former firm Th. Usteri-Reinacher in Zurich, manufacturer of instruments required for barogoniometry: Goldschmid aneroids and goniometers of his own design”. In other words, Mettler not only continued producing the classic “Goldschmid” aneroid barometers, but also developed his own instrument – the “goniometer” – for barometric methods of altitude measurement. In the 1920s, Mettler’s firm actively advertised its services in manufacturing and repairing precision instruments, as seen in technical journals of the period. The workshop continued Swiss traditions of fine mechanics well into the mid-20th century, although with the rise of electronics and new technologies the Goldschmid system barometers gradually lost their practical relevance.

Hans Mettler carefully preserved the accumulated knowledge of several generations. His father, who had worked in the Swiss Meteorological Service, assisted him after retirement by checking instruments, handling correspondence with clients, and thus linking the family business with science. Mettler himself, beyond his practical work, showed a broad range of scientific interests: he published articles and books on hydrometry, pursued astronomical observations, mathematics, and even the study of comets. In one of his writings he remarked, “I have always engaged in mathematical problems, even after I took over the instrument workshop in 1916”. This statement underscores the continuity: from Johann Georg Oeri through Jakob Goldschmid and all subsequent masters to Hans Mettler, there runs a thread uniting craftsmanship with devotion to science. It was this blend that allowed a small Swiss enterprise to last for more than a century, leaving a distinct mark in the history of scientific instruments.

The history of the Goldschmid barometer is a fascinating succession of inventors and engineers. Jakob Goldschmid, building on the foundation laid by Johann Georg Oeri, created a revolutionary instrument that made altitude measurement possible outside of laboratories. His work was carried forward by talented successors: Rudolf Hottinger refined the design and spread it worldwide, Theophil Usteri-Reinacher turned production into an industrial-scale enterprise enriched with new devices, and Hans Mettler carried the torch into the 20th century. Meanwhile, scientific enthusiasts such as Carl Koppe and August Weilenmann contributed their own theoretical and practical advances. The technical evolution of the instrument – from Goldschmid’s earliest models to complex barographs and specialized altimeters – went hand in hand with the lives of these men. Their combined efforts ensured the success of the “Goldschmid barometer” and inscribed it into the history of science and technology as a striking example of Swiss quality and innovation.

Here I would like to share my thoughts on Goldschmid’s use of the aneroid capsule, Lucien Vidie’s invention, during the period when the inventor’s patent was still in force.

Goldschmid was one of the first to create his own version of the aneroid barometer following Lucien Vidie. Already in 1850, at a meeting of the Zurich Society of Naturalists, a “spring air barometer” designed by mechanic Goldschmid was presented. Essentially, at the heart of Goldschmid’s instrument lay the same vacuum capsule (aneroid box) invented by Vidie.

Goldschmid was able to use the idea of the vacuum capsule freely without legal consequences, since he worked in Switzerland, where at that time patent protection of inventions did not exist. (Switzerland spent practically the entire 19th century without a national patent law and only introduced one in 1888.) Thus, Vidie’s patent, valid in France, did not extend to Zurich. Moreover, by the time Goldschmid’s instruments became known outside Switzerland, Vidie’s French patent had already expired (around 1855). It should be noted that history records no legal disputes between Vidie and Goldschmid—unlike Vidie’s loud lawsuits with another inventor of barometric instruments, Eugène Bourdon. Goldschmid likely avoided conflicts because his activities geographically lay outside the reach of Vidie’s patent and did not overlap with Vidie’s commercial interests.

A comparison of dates and priorities: Lucien Vidie received his first patents for the aneroid barometer in 1844, while Jakob Goldschmid began developing similar instruments about five years later—his first aneroids date to around 1849–1850. Thus, Goldschmid was not an independent competitor in the race for invention: he made use of the already known Vidie capsule technology, supplementing it with his own engineering solutions. According to available data, Goldschmid did not file his own patents for barometers—in the absence of a patent law in his country this was not necessary. Instead, Goldschmid focused on refining the design and manufacturing instruments in his Zurich workshop (later the legacy was continued by his successors, the firm Hottinger & Co. and others). After 1855, when Vidie’s monopoly ended, aneroids with the “Vidie capsule” began to be freely produced by various firms across Europe, including well-known Parisian manufacturers (such as Naudet and others). Against this backdrop, Goldschmid’s precise and portable barometers found their niche—they were eagerly used by alpinists, explorers, and engineers for measuring altitude and atmospheric pressure in the field. Goldschmid’s aneroid with micrometric adjustment established itself as one of the most accurate instruments of its era for barometric altimetry, and its principles partly anticipated later improvements of aneroids (for example, the attempt at a fully optical scheme without mechanical transmissions, undertaken by Goldschmid himself around 1870).