Biography and Career

Charles Henry Chadburn (1816–1890) was born into a Quaker family of scientific instrument makers from Sheffield. His father, William Chadburn, had been crafting barometers and optical devices since the 1810s, working in partnership with David Wright. In 1837, the elder sons, Alfred and Francis (the latter bearing the middle name Wright), inherited the family business and founded the firm Chadburn Brothers. Charles joined them in 1841, and the company continued under the collective name “Chadburn Brothers.”

By the early 1840s, the firm had expanded production of optical and mathematical instruments in Sheffield, operating from the Albion Works on Nursery Street, and had established partnerships with major London companies such as Watkins & Hill and Newton & Son. In 1845, Charles H. Chadburn relocated to the industrial hub of Liverpool to open a family branch. His shop and workshop were situated at 71 Lord Street, Liverpool, allowing the firm to reach customers throughout the port city and the broader Northwest region. Thanks to proximity to railways and the port, the Liverpool branch ensured convenient distribution across the country.

By 1847, the company had already earned high recognition, being appointed Optician to His Royal Highness Prince Albert (the Prince Consort). This royal patronage—granted by Prince Albert, husband of Queen Victoria—officially acknowledged Chadburn’s status as a court supplier of optical and scientific instruments.

Between 1845 and 1861, Charles Chadburn successfully managed the Liverpool workshop. He lived nearby, in Egremont (in the Liscard district across the River Mersey), and was a respected member of local society. In the 1850s, he belonged to the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire and later served on the board of Wallasey District Council during the 1860s and 1870s. His Lord Street shop was known for its wide selection of instruments and the high quality of craftsmanship, attracting both local clients and those from the royal court.

Instruments and Barometers

The Chadburn firm produced a wide range of scientific, optical, and navigational instruments typical of the mid-19th century. At the Great Exhibition of 1851 at the Crystal Palace in London, Charles Chadburn was listed as Exhibitor No. 259 in Class X (philosophical, musical, horological, and surgical instruments). The official catalogue of the Exhibition lists Chadburn’s contributions as: “spectacle lenses and glasses, telescopes and microscopes (at various stages of manufacture), agricultural and surveying levels, magnets, steam and vacuum manometers, barometers, syringes, galvanic machines, the Craig charactograph for writing, and more.” This variety highlights the diversity of the firm’s production — ranging from optical to meteorological devices — and confirms that barometers were among its key products.

Chadburn was particularly known for his mercury stick barometers, designed in elegant mahogany cases typical of the Victorian era. These instruments featured an arched silvered brass scale at the top, often engraved with a vernier for precise readings, a built-in thermometer, and a cylindrical mercury cistern at the bottom. The scale was usually marked with standard weather indicators (Stormy – Rain – Change – Fair) and bore the full signature of the maker. Before 1861, Chadburn’s barometers proudly displayed the inscription: “Chadburn, Optician & Instrument Maker to H.R.H. Prince Albert, 71 Lord Street, Liverpool” — an unmistakable sign of royal appointment.

An extant example of a wall-mounted marine barometer from the 1850s bears an ivory scale engraved with: “Chadburn, Optician to H.R.H. Prince Albert, Liverpool.” The instrument is fitted with a suspension ring and a long thermometer embedded in the wooden case.

After Prince Albert’s death in 1861, the inscription changed. Later instruments were signed more simply, such as “Chadburn Bros, Opticians &c, Sheffield & Liverpool.” A notable example of a scientific (observatory-style) barometer bears side panels engraved with the initials “C.H. Chadburn,” filled in with black enamel. By the early 20th century, some pocket aneroid altimeters and barographs appeared under the Chadburn’s Ltd label (with a Liverpool address at 47 Castle Street), but the finest and most historically valuable instruments remain the early mercury barometers from the Victorian era.

Marine barometers were another specialty of Chadburn’s workshop. These were designed for shipboard use, with robust mounts and scales calibrated in inches of mercury, useful for weather forecasting at sea. One known model — possibly an exhibition piece — featured dual scales for readings at 8 a.m. and 8 p.m., in line with Admiral FitzRoy’s recommendations around 1857. This barometer had a fully exposed mercury column inside a glass-covered case, allowing a clear view of the mechanism — likely intended for display in the shop window or for a wealthy collector.

In addition to barometers, Chadburn earned praise for his optical instruments — including refracting telescopes (signed “Chadburn, 71 Lord St. Liverpool”) and compound microscopes. The firm also ventured into military technology: in 1860, Charles Chadburn patented an innovative rifle distance gauge — a compact pocket device with a thread and scale that helped infantrymen estimate the distance to a standing figure (up to ~900 yards) for accurate aiming. An original example of this gauge is now preserved in the collections of the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich.

Reputation, Exhibitions, and Inventions

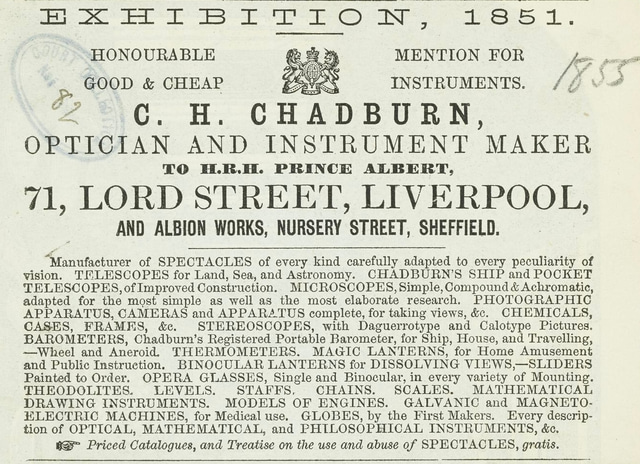

By the mid-19th century, the name Chadburn was well-known among professional opticians and scientific instrument makers. At the Great Exhibition of 1851, the Chadburn Brothers’ display attracted attention from the jury. For the quality and variety of their instruments, the firm was awarded an Honourable Mention, a distinction proudly noted in their later advertisements. They even reproduced a drawing of their exhibition stand, which they later recreated inside their Sheffield showroom.

The royal appointment further boosted Chadburn’s reputation. The title “By Appointment to H.R.H. Prince Albert” allowed the firm to advertise itself as a personal supplier to Queen Victoria’s husband. Historians confirm that Chadburn supplied Prince Albert with scientific instruments up until the prince’s death in 1861. Contemporary references describe the Chadburns as “notable makers” in the industry. Edwin Banfield’s reference work Barometer Makers and Retailers 1660–1900 identifies Chadburn Brothers as one of the leading barometer manufacturers outside London during the 1837–1875 period.

The Chadburns also acted as retailers. Their shop stocked not only their own products but also high-quality instruments sourced from top London and international makers. This hybrid approach gave them a broad product range and commercial resilience.

Charles Chadburn was also an inventor and patent-holder. In 1858, he was granted British patent No. 732 for “improvements in pressure gauges” — likely relating to steam or vacuum manometers that were manufactured alongside barometers. In 1870, Charles and his son William jointly filed patent No. 2384 for “improvements in mechanical telegraphs and the working fluid used therein.” These devices were early shipboard engine room telegraphs — instruments for transmitting orders from the bridge to the engine room — and the patent referred to a special non-freezing fluid to power them.

In March 1860, Charles also registered a “useful design” (No. 4247) for his compact rifle distance gauges (mentioned above), which gained some popularity among sportsmen and volunteer riflemen. Together, these inventions demonstrate that Charles Henry Chadburn was not just a merchant, but a skilled engineer contributing to the advancement of scientific and mechanical instrumentation in the Victorian era.

Connection with Prince Albert

Charles Henry Chadburn’s direct connection with Prince Albert, the Prince Consort, is well-documented. In the 1840s and 1850s, Prince Albert — a known patron of the sciences and engineering — showed personal interest in instruments and innovations. Around 1847, the firm Chadburn Brothers received a royal warrant appointing them as Opticians to His Royal Highness Prince Albert. From that point onward, Chadburn’s advertisements prominently featured this title.

At the Great Exhibition of 1851, where Prince Albert served as chief organizer, Chadburn Brothers of Sheffield and Liverpool were listed among the official exhibitors. Their inclusion in the catalogue, along with the royal designation, clearly confirmed their elite status. The firm’s contribution to the Exhibition earned them an Honourable Mention and the privilege of referencing their award and connection to the Prince Consort in marketing materials.

After Prince Albert’s untimely death in December 1861, Charles Chadburn lost his most prestigious patron. However, the reputation built during this period helped the firm continue to thrive. Instruments manufactured before 1861 often retained the full inscription “Optician to H.R.H. Prince Albert,” which remained a mark of excellence and royal recognition.

It is worth noting that both Prince Albert and Queen Victoria took a personal interest in precision instruments, often commissioning barometers and thermometers for royal residences. According to auction house documentation, Chadburn Brothers were indeed suppliers of scientific instruments to Prince Albert, further validating their royal connection. This status not only boosted the firm’s credibility but also firmly placed Chadburn’s name in the history of royal scientific patronage during the Victorian era.

What Became of the Business After 1857

By 1857, Charles Chadburn was 41 years old and his Liverpool operation was at its peak. The firm was very much a family business: by the late 1850s, his son William Chadburn had come of age and was preparing to continue the family tradition. In 1861, Charles formally separated the Liverpool branch from the Sheffield parent firm, establishing it as an independent business under the name Chadburn & Son, with William as partner. This move coincided with the loss of their royal patron (following Prince Albert’s death) and may also have reflected Charles’s decision not to participate in the 1862 London International Exhibition under the Sheffield banner.

William Chadburn proved to be a talented inventor and businessman. Even before 1870, while still working alongside his father, he patented several innovations, including the ship engine room telegraph, a device that allowed communication between the bridge and engine room on large vessels. This invention was soon adopted across the British shipping industry.

In the 1870s, the business flourished and expanded. New offices were opened in London (at 105 Fenchurch Street), and possibly in Glasgow and Newcastle as well. By 1875, Charles Chadburn retired from active business; the partnership Chadburn & Son was officially dissolved, and the firm continued as Chadburn & Sons, now involving William’s own sons — the third generation of Chadburns.

Under William’s leadership, the company focused increasingly on marine communication equipment. Their ship’s telegraphs — mechanical devices for sending commands from bridge to engine room — became industry standard. William worked closely with major shipbuilders, including Thomas Ismay, founder of the White Star Line. Chadburn telegraphs were installed on many of the world’s great steamships — including the RMS Titanic, launched in 1912, which was equipped with Chadburn engine room telegraphs and steam whistles.

By the end of the 19th century, Chadburn’s company specialized almost exclusively in marine signaling systems. In 1898, it was formally incorporated as Chadburn’s Ship Telegraph Company Ltd., with branches in Liverpool, London, and Belfast. Remarkably, the business survived well into the 20th and even 21st century, adapting to manufacture controls and transmissions for both marine and land-based applications.

As for the original Chadburn Brothers firm in Sheffield, it operated in parallel until at least the 1880s. After Charles’s departure in 1861 and the deaths of his elder brothers (Alfred in 1887 and Francis Wright in 1890), the Sheffield branch declined. By 1893, the remaining business was said to be owned by a W.T. Morgan, described as a “nephew of the Chadburn brothers,” though the family link is unclear. In any case, the original workshop faded from prominence, and the Liverpool operation led by Charles’s descendants became the true successor to the Chadburn name.

Catalogs and Surviving Materials: Complete commercial catalogs from the mid-19th century are rare, but several sources confirm the product range. The Official Catalogue of the 1851 Great Exhibition provides a detailed list of Chadburn instruments, including barometers. Additionally, the Science Museum Group (UK) holds a trade advertisement from 1851 naming Chadburn Brothers as “Optical, Mathematical and Philosophical Instrument Makers to H.R.H. Prince Albert.”

Descriptions of barometers by Chadburn survive in museum collections and auction records. Edwin Banfield’s authoritative directory notes Chadburn Brothers as a noteworthy barometer maker outside London (1837–1875). The UK Meteorological Office once held a station barometer by Chadburn, and several rare examples have appeared in collections such as the Barometer Museum of Devon. Victorian-era mercury stick barometers with engraved ivory or silvered brass dials signed “Chadburn, Liverpool” still surface in antique auctions. One such marine barometer (dated 1837–1875) was auctioned in Birmingham in 2007 with an estimate of £1,800–2,500 — featuring a polished mahogany case, precision vernier, and engraved signature.

These surviving instruments are historical artifacts in their own right, reflecting not only the scientific progress of the age, but also the enduring legacy of Charles Henry Chadburn — a master craftsman, engineer, and founder of a lineage that spanned three generations and helped shape British instrument-making through the Victorian era and beyond.