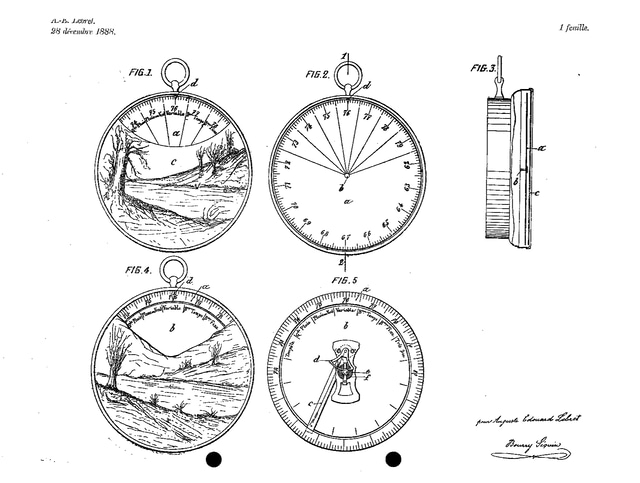

In the horological world of late 19th-century Paris, the name Auguste Edouard Lebret, though not as renowned as Breguet or Reymond, occupies a distinctive place. His work stood at the intersection of precision mechanics, pedagogy, and refined decorative arts. Lebret was not merely a watchmaker — he was an engineer-educator, intent on transforming his instruments into tools for learning, including for the youngest observers.

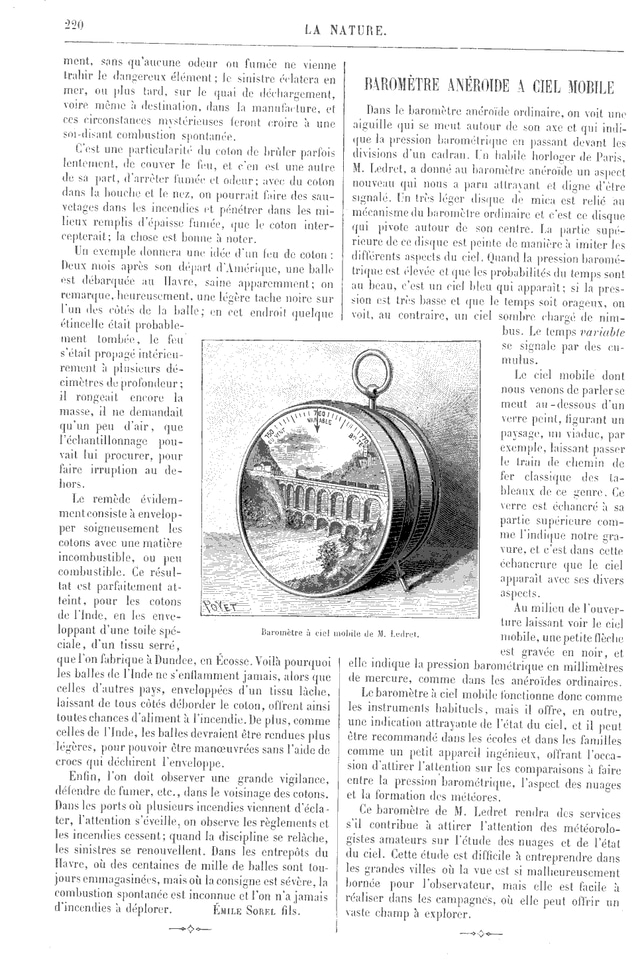

It was Auguste Lebret, working from 111 rue de Sèvres in Paris, who created one of the most unusual aneroid barometers of the Belle Époque — the baromètre à ciel mobile, or “barometer with a moving sky.” This instrument not only measured atmospheric pressure, but also offered a visual representation of the sky’s condition, simulating meteorological changes directly on its dial.

In 1888, La Nature — the leading French popular science journal of the time — published an article titled “Baromètre anéroïde à ciel mobile” (La Nature, 1888, vol. 1, p. 220). It described a modified aneroid barometer featuring a rotating transparent disc painted to show various states of the sky: blue for fair weather, stormy for low pressure. The concept was brilliantly simple, yet visually compelling and pedagogically effective — especially for use in schools and domestic education.

The author of the article praised both the engineering ingenuity and the aesthetic merit of the device. The barometer with a “moving sky” was recommended for use in schools and rural areas, where users could observe the sky and compare its appearance to atmospheric pressure readings.

However, the article contained an error that would later confuse researchers: the maker of the instrument was named as “M. Ledret.” In fact, the barometer was the work of Auguste Lebret, whose name and workshop at 111 rue de Sèvres are well attested in numerous primary sources. This typographical mistake, introduced by the editorial team at La Nature, was later repeated in many publications, and even entered some catalogs. Nevertheless, sufficient documentation now allows us to firmly establish the true authorship.

Lebret began his career as a horloger-fabricant — both a watchmaker and a producer of scientific instruments. His workshop was located on the ground floor of the historic Hôtel Choiseul-Praslin, at number 111 on rue de Sèvres. This was an active artisanal district, home to dealers in clocks, barometers, telescopes, as well as boutiques and institutions of bourgeois science and commerce. In trade directories, Lebret was often listed as a fabricant d’instruments, reflecting his contribution not only to horology but to the development of precision instruments in general.

Beyond conventional timekeeping, Lebret specialized in astronomical regulators and electrically wound mechanisms, reflecting his deep engagement with scientific and precision disciplines.

A major highlight of his career was his participation in the Exposition Universelle of 1900 in Paris. In the official catalogue, he appears as:

Lebret (Auguste), à Paris, rue de Sèvres, 111 – Pendules astronomiques et de voyage.

For his exhibition of astronomical pendulum clocks and other precision devices, he was awarded a bronze medal, as recorded in the official registry of awards — a significant recognition of his technical accomplishments.

Lebret showcased instruments that combined mechanical elegance with scientific rigor, including models incorporating automatic electric winding systems.

He is particularly known for his patent concerning the electric winding of clocks and pocket watches. The patent was filed on December 7, 1900, and granted in November 1901. It describes a mechanism using a conventional electromagnet and pivoted armature to wind the mainspring of a clock or pocket watch. The system was designed to wind the spring either once per minute or once every four minutes. A detailed analysis of the patent refers specifically to the “one-minute version.”

The winding process was initiated by a switch composed of two spring plates, triggered by a cam on an extended arbor of the second wheel. This attracted the armature, advancing the mainspring drum by one tooth. Due to the frequent winding (once per minute), the gear train was greatly simplified, consisting of just three wheels: the mainspring barrel, the second wheel (controlling switching), and the escape wheel.

While conceptually innovative for its time, Lebret’s design faced serious practical limitations, highlighting the gap between theoretical invention and commercial feasibility in early electric horology.

The main shortcomings of Lebret’s system included: • External power source: The system required a large external battery, specifically a Leclanché dry cell, comparable in size to a pint bottle — making it impractical for household use. • High current consumption: The electrical circuit was described as “poor” due to the low resistance of the coils, requiring high current. This stood in stark contrast to more successful designs that followed, which used higher-resistance coils and drew far less current, making them compatible with small internal batteries. • Nonstandard time-setting mechanism: The simplified three-wheel train meant that the motion work was nontraditional and, in the only known example, completely missing. There was no standard hour wheel, and the method for initially setting or re-setting the spring after a full run-down was unclear — no winding square was provided.

These fundamental flaws prevented the invention’s adoption and commercialization. In contrast, other systems such as those by David Perret or Brillié soon overcame such obstacles and entered the market. The case of Lebret illustrates the experimental and often trial-and-error nature of early electric horology, in which many promising concepts failed to become viable products.

The only known surviving example of Lebret’s clock using this system is miniature in scale.

A photograph of the original instrument is available on the Clockdoc platform: https://clockdoc.org/default.aspx?aid=6022. The clock is remarkably small — the movement measures only 4 cm in diameter. It may well have been the first electric clock of such compact dimensions. The case includes a decorative aperture for a flexible power cord, linking the mechanism to its external battery. Its uniqueness and the absence of certain components (the switching mechanism, motion work) strongly suggest that it was an experimental or prototype piece.

Auguste Lebret was a craftsman at the intersection of engineering and scientific outreach. His barometer with a moving sky — a graceful fusion of meteorological instrumentation and visual education — was far more than a decorative curiosity. It was a serious educational device, meant to spark public interest in weather observation, especially in schools and rural communities. The mistaken name printed in La Nature sadly deprived him of some of the recognition he deserved. Yet thanks to the 1900 exhibition, his patents, and the few surviving instruments, we are now able to restore both his name and his legacy.